RK: Hello, and welcome back! Thanks for your patience during our little hiatus. It turns out that moving states and changing jobs really makes it difficult to do, well, almost anything else. But we’ve returned to bring you a short missive, perhaps appropriately, On Error.

Early on in my career at Christie’s, my colleague Christina told me that it was part of the job to get used to public humiliation — because it was inevitable not only that you would make a mistake, but that your mistake would make it into print (and then get directly mailed to a large number of people whose opinion you value). I’ve occasionally reflected since then on the relationship between print and error, particularly as so many early modern books end with short (or long) lists of errata. At least it’s a balm to know I’m not alone.

Print has a permanence and immediate multiplicity that makes errors which might otherwise feel like a “whoopsy-daisy” into something much more painful, even as they are, of course, inevitable. A slip of the tongue? That’s one thing. Scribal errors? That’s its own field, but at least they only happen one at a time. An error in print can mean an error in hundreds or more copies of something, all at once! Ouch. And some dork like me is going to point it out every time I catalogue one of your books. This is not only a problem for writers. Think about the poor, nameless compositor of Shakespeare’s First Folio who is known only for sucking at typesetting compared to their colleagues.

Working on the Columbus Letter last year brought this to the fore for me. And not only because I was afraid of my own potential mistakes. The entire story of Columbus and his reception is full of errors, mistakes, fakes, and forgeries. So much so that he is given as a paradigmatic example of what Umberto Eco calls “the force of falsity” in his essay of the same name:

Such then is the force of truth. But experience teaches us that often the imposition of truth has been delayed, and its acceptance has come at the price of blood and tears. Is it not possible that a similar force is displayed also by misunderstanding, whereby we can legitimately speak of a force of the false?1

Part of his point is that Columbus’s accomplishments, such as they are, were achieved basically because he was wrong. He believed, extraordinarily, that the size of the Earth was much smaller than it actually is, and insisted until his death that the place he had gone across the Atlantic was Asia. But his wrongness somehow got him to the right place.

This is a dramatic example (and one I’ve been revisiting recently because I am working on a talk about wrongness and early modern science). But it’s also true in the field of bibliography that errors can be, in their own way, salutary. Now, we catalogers and book historians gobble up fallen type, evidence of stop-press corrections, and signs of all the various mess-ups which can teach us so much about the process of making books. Errors allow us a peek behind the curtain of the finished project.2

JWD: Rhiannon, that was a really lovely introduction, and I’ll add my apologies to yours as well. I just felt, well, subsumed by life these last few months, but I am thankful that you kept nudging me to get back in to the newsletter. Let’s call it our summer vacation, shall we?

That opening is incredibly generous and I am going to take your lead and muse on error in my own professional life. We both work in a field where we are surrounded by intensely intelligent and engaged people that generally have strong viewpoints and can be, well, argumentative. This is bad and good, depending on the day and what words have recently escaped my mouth or my pen or my keyboard. But, thanks to some early minor (but tough for me) lessons early on, I learned that it’s dangerous to assume that you are the smartest person in the room - and by extension that everything that you say, despite how carefully researched - might not be right. There is a fine art to “pulling your punches,” one learned over time, which you all have likely seen me do in presentations or publications. It’s less the avoidance of error, and more the admission that our work as bibliographers (and for me as a librarian) is never really done, even after we’re no longer in this plane of reality. It’s a practice, friends.

Perhaps the most difficult part for me has been admitting that I don’t know everything, and want to learn something. I’ll always be eternally grateful to my former colleague, Jamie Cumby, for teaching me the basics of collation - which she did because I asked her. I do think that touches on one of the two great strengths of this work, Rhiannon, that people are perennially curious, and that people on balance are generous with their time and expertise. They have been with me, starting early in my career when Bill Reese answered what seemed like a zillion questions for me, and continues now with the ever-generous Nick Wilding and Paul Needham and Scott Clemons (and you too, Rhiannon!) As a matter of fact, you helped me land on the correct pluralization for three copies of Sidereus Nuncius, among other things.

A reminder of this was made plain when Jamie and I worked on our article about the print run for Principia, which made assertions about a book because, well, let’s say there were a lot of assumptions made on the part of the authors - one of whom is a highly regarded historian in the field. I’m not saying that we settled that two hundred year old debate, though!

When I was deep in the work on Sidereus, I built a chart tracking all the known Galilean corrected copies of the book and their corrections. In that list, I included the Arsenal copy of the book, printed on ordinary paper, with evidence of folding for diplomatic mail - it’s the only other copy with that evidence other than LHL’s ordinary paper copy (that we know of - still pulling punches, even here). BUT I was wrong - it’s not annotated in Galileo’s hand (which OF COURSE Paul noted, but I, a goof, overlooked), but all of the public facing material references fifteen copies rather than fourteen with Galilean corrections. Sigh. I am human, and the chart is now corrected, but still, it stings.

And that sting comes in the knowledge that those statements linger on, despite our best work, leading to potential messes for our successors to clean up. Alas.

Some of you all know that I collect southwestern art, and Navajo textiles in particular. There’s a tradition among the Diné that they make each of their weavings imperfect - as weaver Pearl Sunrise says: “The great spiritual being is perfect but we are just kind of a remake of the being, so, we can't be perfect and that irregularity that we put into our creativity honors that.” Maybe that’s the best way to think of error - as intensely human, and perhaps that’s why errors in our field - bibliography and book history - is so exciting now. The printed word is supposed to be this almost infallible thing, when really, it is anything but - filled with error and failings and (as I bet your science talk will point out, RK) bad reasoning.

Two Cool Things

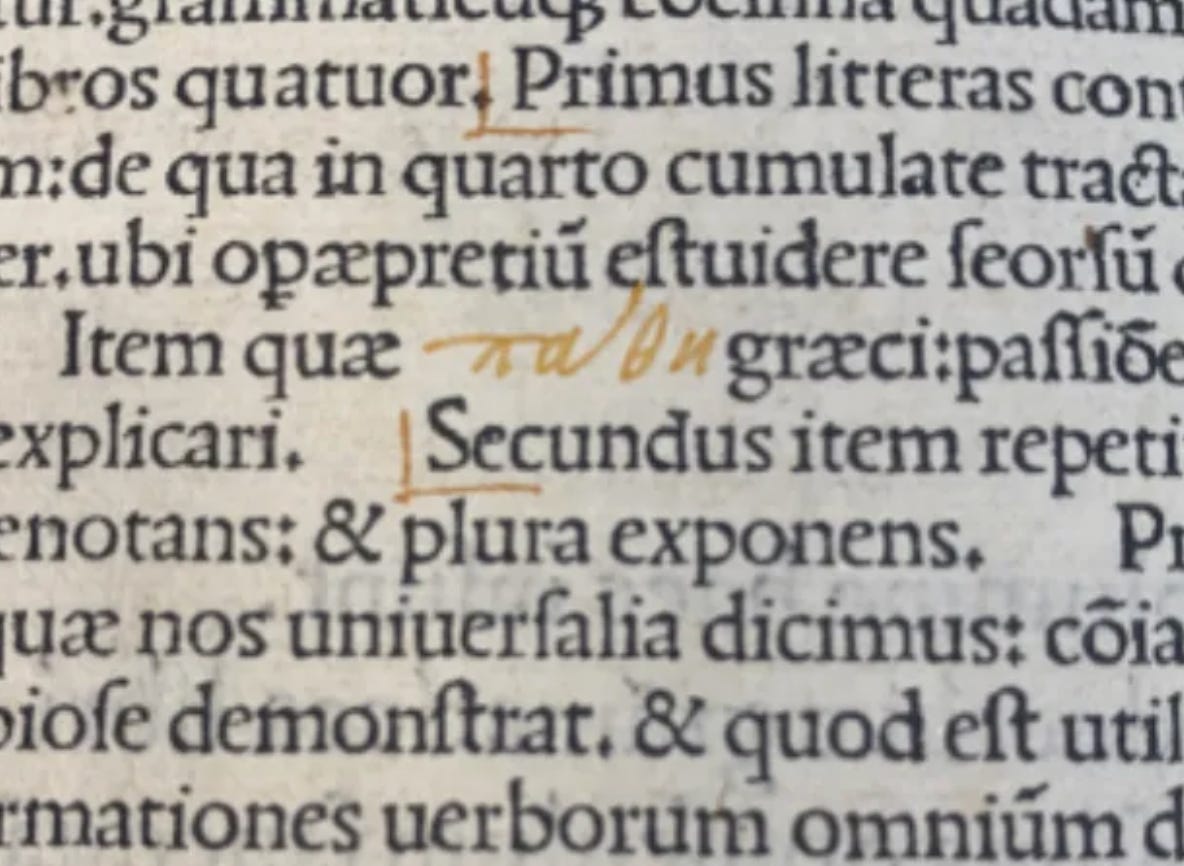

RK: One of the last books I catalogued before leaving New York was the 1495 Aldine edition of Theodore Gaza’s Greek grammar. A much studied, much adored entry in Aldus Manutius’s Greek printing program, it was book I knew about, but had never before seen up close.

Something that caught my eye right away was the blank space left in the Latin preface for a Greek word to be filled in. This is not at all unusual for incunables — not every printer had Greek type or the Greek literacy to use it. But WHY ON EARTH would Aldus need to leave space for a Greek word to be filled in?? This question stuck with me as I finished collating and began my reference checks.

Multiple bibliographies all noted that their copies had the blank space, and that it was filled in. Intrigued, and blessed to live in the internet era, I checked all the available digital facsimiles of the book:

Every single copy had the word filled in — and in the same distinctive hand. This is when I started getting excited, because the only reasonable explanation for such a situation, to me, was that the correction was made in Aldus’s workshop. Help from a few generous friends who provided emergency bibliographic assistance confirmed my suspicion: it was indeed Aldus’s hand.

How could it be that nobody had noticed this before? Well, it turned out, of course, that someone had. Published only last year, Geri Della Rocca de Candal’s monumental “Manus Manutii” in Printing and Misprinting3 treats not only this book, but Aldus’s workshop correction practices and their surviving evidence as a whole.

In fact, quite a few of Aldus’s books were corrected by his own hand, which reveals, as Della Rocca points out, “a character increasingly reminiscent of a perfectionist and a control freak (a bad combination).”4 I discovered that there were several more Aldine corrections in my copy — and that I had missed Aldus’s hand in the copy of his Theocritus I sold back in 2018. Mistakes on mistakes…

The essays collected in Printing and Misprinting invite reflection on not only all the ways that errors get made, but how they can be corrected. Beyond the standard errata list, you can find painstaking manuscript corrections like Aldus’s, printed correction slips (maybe even more painstaking?), whole cancelled leaves and gatherings, corrected issues, and more. There is redemption.

The article, by the way, also answered my initial question of why Aldus even needed to leave a blank for a Greek word. His own Greek types were too tall to fit on the line with the Latin text of the preface! How much we can learn from someone else’s mistakes, not only our own.

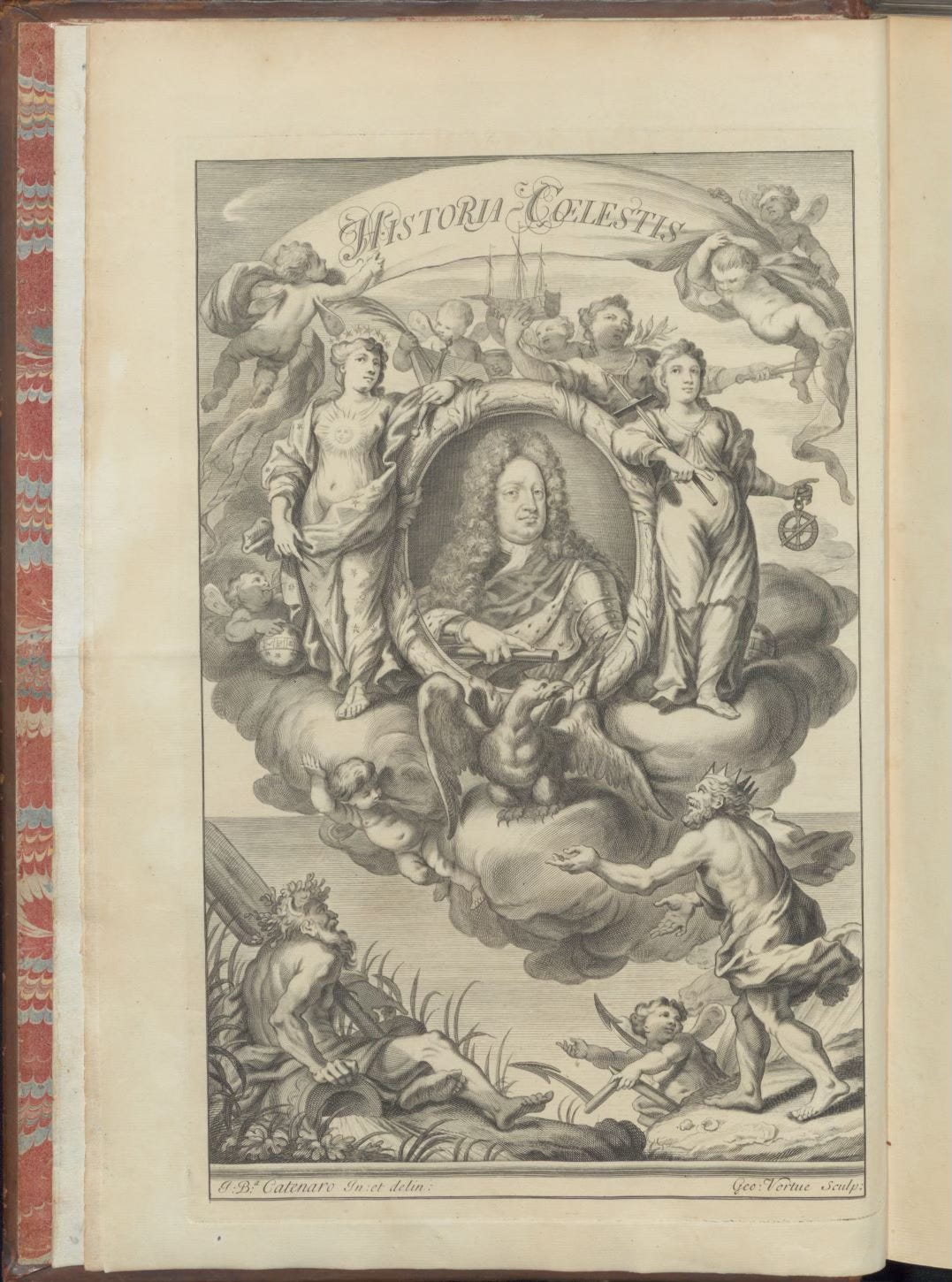

JWD: This concept of error has been rattling around in my brain, and I keep settling on one Cool Thing in particular, related to the topic - the suppressed 1712 edition of John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis, printed against Flamsteed’s wishes - because Flamsteed saw his work being published as premature and full of error.5

Allow me to poorly retell the story - Isaac Newton is President of the Royal Society, and Flamsteed is the Astronomer Royal. Newton desires access to Flamsteed’s preliminary results from the Royal Observatory, which Flamsteed gives him to a limited extent - but this is simply not enough data for Newton to achieve his aims - a revised edition of his Principia. The ensuing argument turns very public very quickly, and grows to include Edmund Halley and the Crown itself (in the person of Queen Anne and Prince George of Denmark).

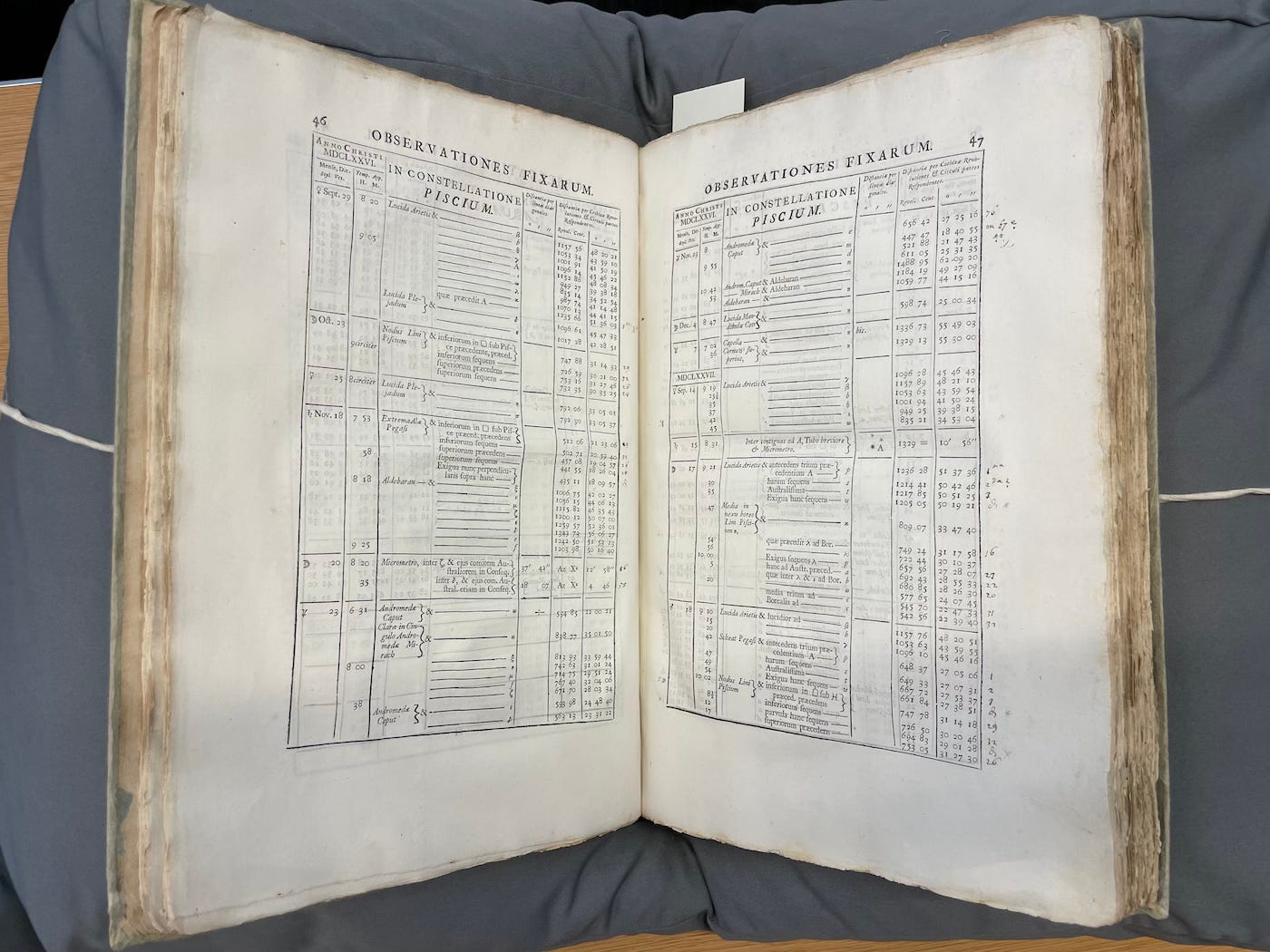

This is a drastic oversimplification, but Flamsteed at the base objected to the premature publication of his results (the positions of celestial objects - stars, planets, &c) because he and his assistants made multiple observations of each of these objects using as many of the instruments they had on Greenwich Hill, and then were mathematically correcting the results for the most precise and accurate observations and positions they could provide - key for what was Flamsteed’s charge as Astronomer Royal: “forthwith to apply himself with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so-much desired longitude of places, for the perfecting the art of navigation.”

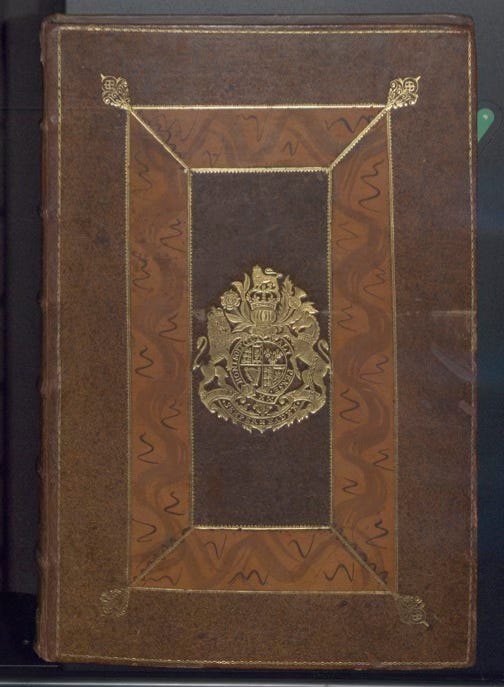

So, then, the publication of these observations over Flamsteed’s objections violated his understanding of his commission, but also spoke to and highlighted intellectual property, priority, and ownership in late 17th and early 18th century Britain. The 1712 edition of the book appeared over Flamsteed’s very public and very loud objections, and was mostly given as diplomatic gifts, though more than a few apparently were for sale, as Emma Louise Hill is working on (NB - we’re also working on a full piece about the book, which will include a census (there are 59 copies she knows of). We hope!).

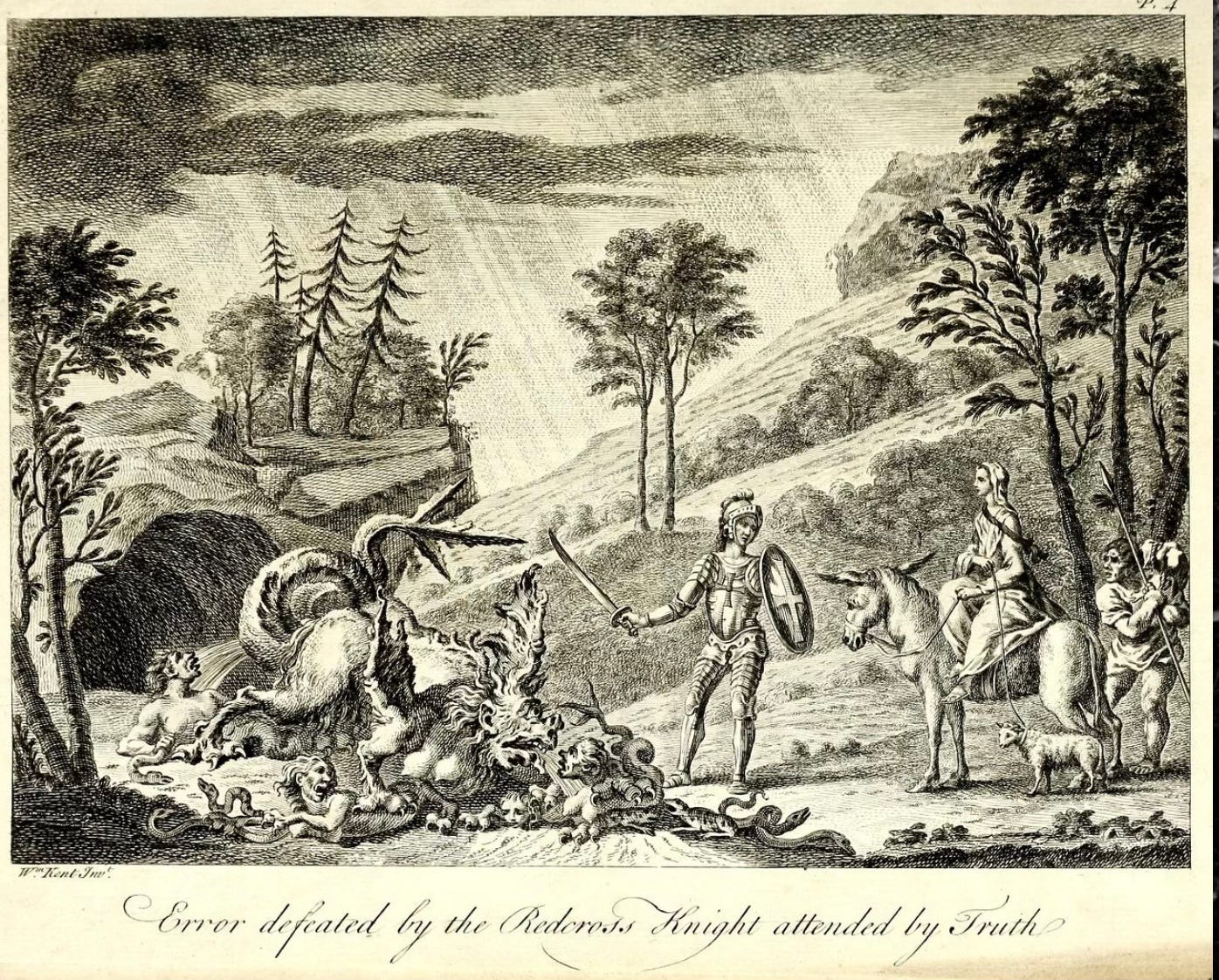

The book appears, as I say, and then in early 1716, after the accession of George the first (and the attendant fall from favor of Newton), Flamsteed was gifted the remaining copies of the work, which he burned in a pyre near the observatory! He called that… a “Sacrifice to TRUTH” which seems really on the nose for this newsletter.

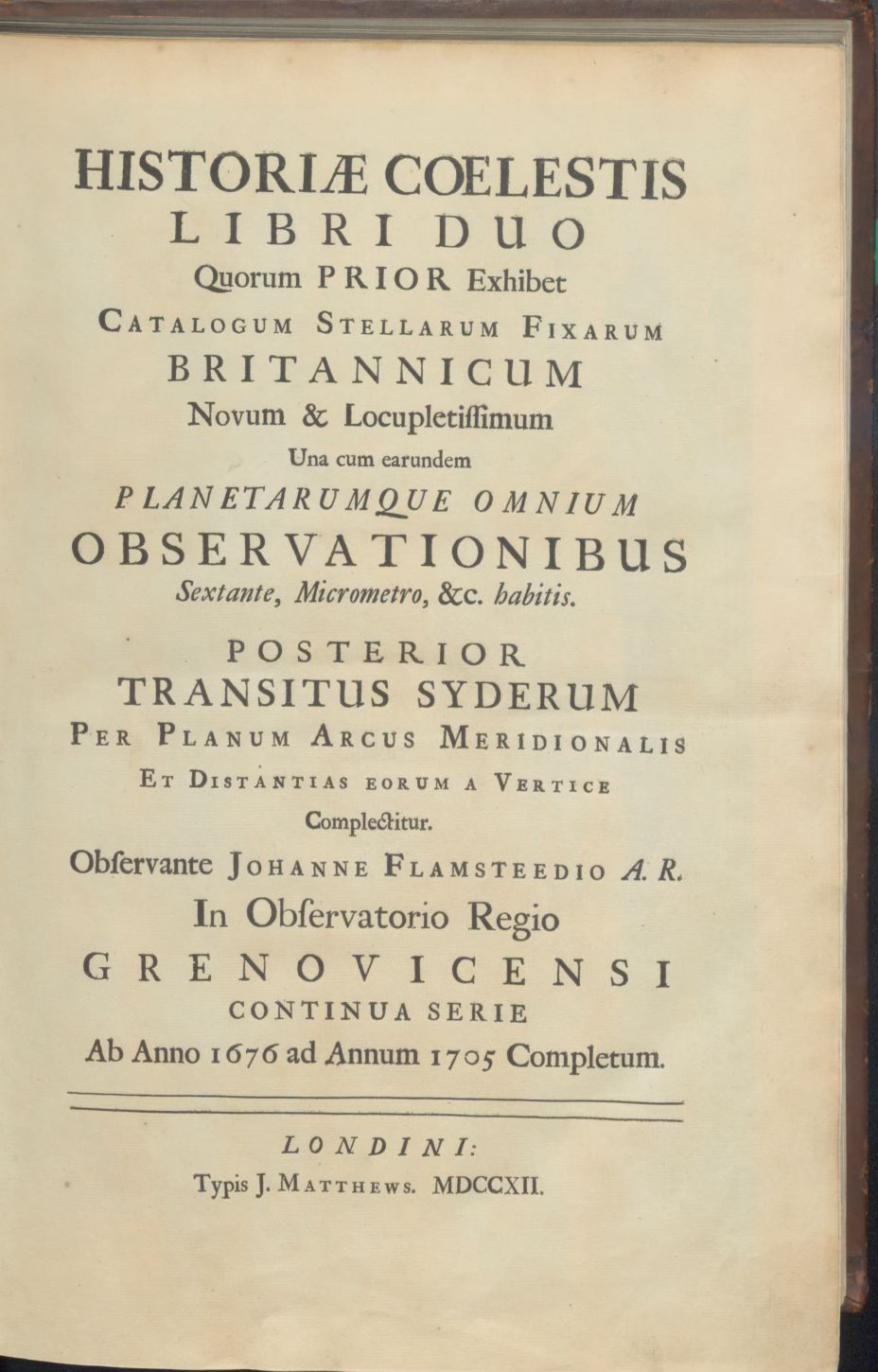

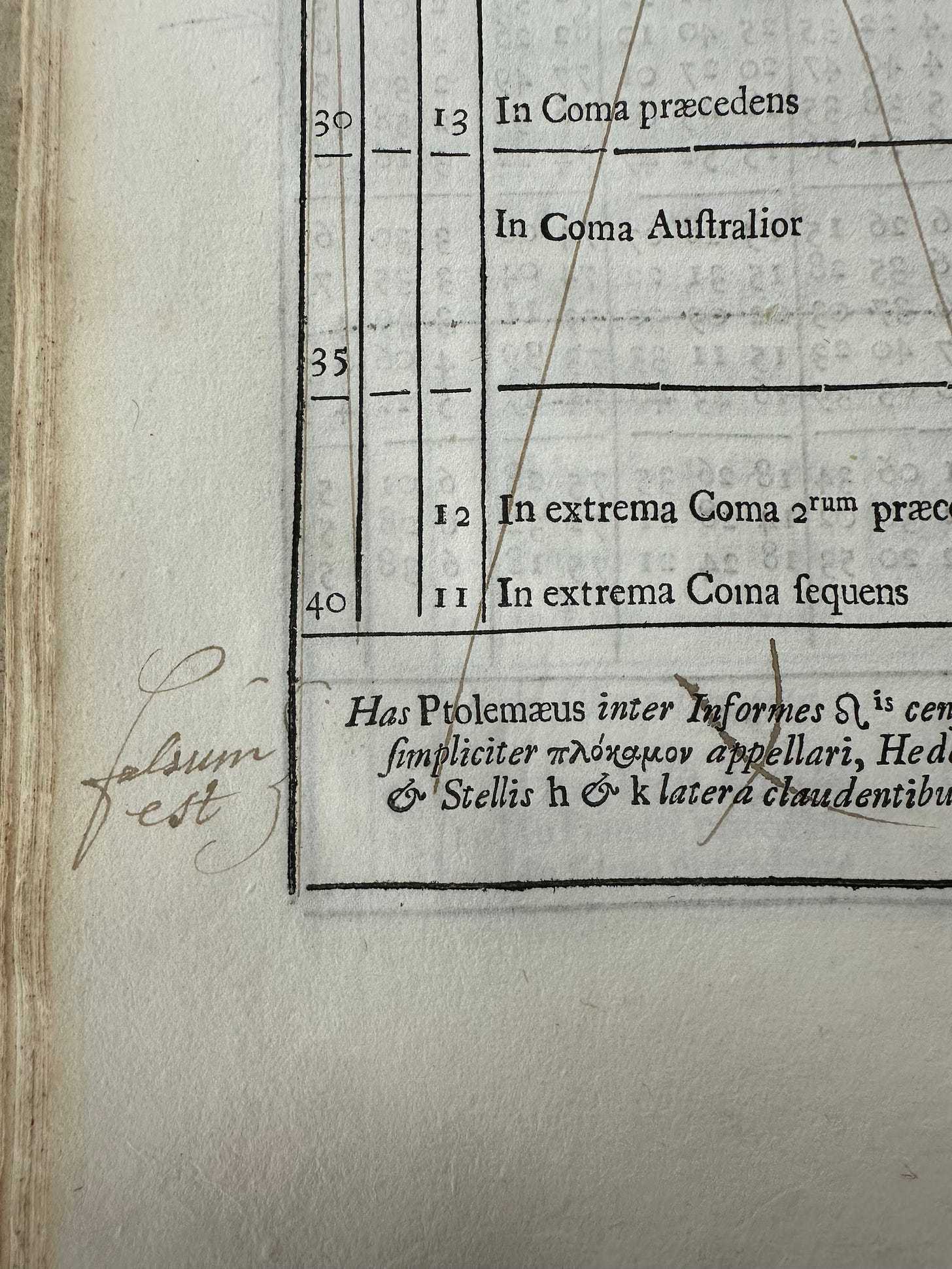

So I feel like that’s at least a gesture at macro concepts of error - uncorrected data, and the concept of accuracy and (as Flamsteed called it) TRUTH, but even in this edition of the book, there were still micro errors that arose, with their attendant corrections, and such, perhaps best illustrated in the copy that Owen Gingerich had of the 1712 edition of Historia Coelestis, which consisted of only the sections Flamsteed objected to, with corrections in Flamsteed’s own hand that Gingerich claims was the copy sent to one of Flamsteed’s assistants, Abraham Sharp. I got the chance to examine his copy earlier this year, which is amazing.

I also had the pleasure of seeing the ex-Halley proof copy, with his CORRECTIONS at the Caird Library, which should also get a photo. The divergent idea of corrections and error here… is astonishing to me:

Anyhow, if you want way more information about the 1712 edition and the wild story around its production and suppression, Adrian Johns and I did an After Hours about it:

I’ll take your lead again, Rhiannon, and add in a modern book that speaks a bit to error and folly that I finished last week. It’s

’ The Believer, which is ostensibly a book about fishing, but really is a book about, well, the long view - success and failure, joy and planning, serendipity and loss. Or maybe just a reflection on being human, and the imperfections and complications that brings, as seen through the lens of fishing. Here’s a quote from my favorite chapter, the one where Coggins is in Norway:When you reel in for the last time, you exit the equation. There’s no fanciful narrative. It’s over. Was it a failure of imagination? Or just a failure? “The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” Elizabeth Bishop wrote. In losing I keep looking for a secret meaning I can’t find. I get to my feet. I head back to the car before it’s too dark to see. The rain is supposed to gall through the night. Tomorrow, the salmon will be swimming up the river.

Current Events

RK: If you’re in or near New York, you still have time to get to the Grolier Club’s wonderful exhibition “Hardly Harmless Drudgery: Landmarks in English Lexicography,” which closes on the 27th. Who doesn’t love a dictionary? Otherwise, summer is feeling a little bit sleepy. But maybe that’s just me!

JWD: Well, I’d like to share that Scott Clemons’ lovely talk on collecting Aldines is up, and is certainly worth watching:

That he wore a UVA and Princeton appropriate tie is not lost on me, I’ll confess, but I really enjoyed one of the kindest folks I’ve ever met sharing parts of his collection. Rhiannon and I had the chance to share a really wonderful morning with him and Aldus around NYABF, and that is a memory I treasure.

Finally, a bit closer to “home,” our new acquisitions show opens at LHL in about a week - our first day is July 25th. We’ll have all manner of new acquisitions on display - artists’ books, the new Sidereus, some amazing bindings, and some new gifts in kind to the general collection, as well as some fellows’ publications. I am excited to have it up and available!

Let’s Get Personal

RK: Since moving, I’m taking it easy. I’m growing tomatoes, hot peppers, roses, dahlias, and an assortment of other flowers and herbs. I’ve also been cataloging some really great books, a few of which you might have seen on my instagram — but some will surely appear here in future issues. Beginning in the autumn, I’ll have some travels and talks to share with you.

JWD: Lord, it’s been a crazy summer so far. I’ve been to Santa Fe (limited bibliophilic activities this trip), but did visit a hot spring and was invited to some of the dances at Hopi(!), I’ve been to Las Vegas, and a few other more personal things. I still cannot really recommend a visit to Vegas, but the Neon Museum is worth an (after sundown) visit if you find yourself there.

Conclusion

RK: In Printing and Misprinting, Anthony Grafton writes that “the kingdom of error in early modern Europe was as vividly real as the Kingdom of Satan. It was located not in the bowels of the earth but on its surface, in the shops of printers.” It is certainly also vividly real to me, and sometimes it feels like it is in my office. I try to avoid the truly egregious errors, but it seems like the little ones still slip into the gaps.

JWD: Well, I hope our readers haven’t gotten to this point in the newsletter and determined reading to the end was an error. It’s nice to be back, and Rhiannon, what can our good readers look forward to next month?

RK: we’ll be riffing a bit On Training!

Eco in “The Force of Falsity,” collected in his Serendipities: Language and Lunacy, translated by William Weaver. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

a great example of this is Claire M. Bolton’s 2016 monograph on one of my favorite early printers: The Fifteenth-Century Printing Practices of Johann Zainer, Ulm, 1473–1478. Inventive but perhaps a bit sloppy, his books give a wonderful look at the printing practices of the incunable era.

Geri Della Rocca de Candal, Anthony Grafton, and Paolo Sachet, eds, Printing and Misprinting: A Companion to Mistakes and In-House Corrections in Renaissance Europe (1450-1650). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

In my mind, if you are going to be a micromanager, you’d better be a perfectionist (but this may be revealing more about my own bad qualities than I ought to share).

This story is explored in-depth in chapter 8 of Adrian Johns’ Nature of the Book, (Chicago, 1998). There remains to be more bibliographical work done on the 1712 edition, and I am hoping Emma Louise Hill and I can tag team that in the middle term.