On Curiosity

It killed the cat. But it might work for us!

JWD: I’m surprised, Rhiannon, that we’ve not talked about curiosity in the newsletter yet. But, we are now, and for me the concept of bibliographical and professional curiosity goes back to the very beginnings of my career. I taught history in a high school for a few years before going to library school, and when I determined that was not what I wanted to do long term, I wanted to find a profession that was for people with outsized curiosity (as I like to think I am). Librarianship, and by extension bibliography, is very much the right choice for me. I want to know about lots of things, understand cultures, and think critically about material objects. I get to do this almost every day as I research, describe, and catalog books. When I talk about this work, I always think of Christopher de Hamel’s joyful interrogation of manuscripts and his infectious enthusiasm to know about a manuscript in front of him:

Sitting down with a book for the first time is a deeply curious endeavor - both my own curiosity, and the curious methods and routines bibliophiles engage in when we “meet” a book that is new to us.

“Where did you come from? Are you complete? Who owned you?” I sometimes mutter these under my breath as a look at and interrogate a book. Close looking, attended by skepticism and curiosity can tell us much about a book if one knows what to look for. If one is willing to be open and curious and patient, a book as an artifact can tell us much about the life it has lived, and the environment in which it was produced. This knowledge is dearly gained through a willingness to be wrong, to learn, to be taught, and (again) to look. I’d argue that those are all important parts of curiosity generally, but also the curiosity I hope we all share as people who love the book and printing as material evidence. Close looking as a part of my own curiosity came before my serious work as a bibliographer, when Rika Burnham came to Crystal Bridges, and we spent a day doing close looking at paintings in the collection.

I teased the curious nature of our work, often seen by others as arcane, pointless, and a physical manifestation of pedantry. Well, as is so often my choice, I’d offer this Tanselle quote as a rebuttal:

We regard it as perfectly normal that people write verbal accounts of the physical properties of paintings and drawings, buildings and sculptures, vases and goblets. Because these works of art and craft use physical media, any comments on their physical characteristics are comments on their artistry as well and are thus a form of art criticism. Books, however, are not as commonly approached in physical terms as constituents of material culture, since they exist largely for the purpose of transmitting verbal (or musical or choreographic) texts; and many persons who wish to read and appreciate those texts do not consider the physical aspects of books relevant to their concerns.1

Although as I write this, I can see the toolbox (yes I have a literal toolbox) on my desk with the particular tools of our work - which some might see as curious! I won’t extol the Schaedler Precision Rule again, but it sits in there, along with a cloth measuring tape, a really good loupe (which I use more and wince as I get older), a UV light, and a couple of Staedtler erasers too, and 100% cotton strips to mark pages. They do look rather, well, curious all sitting together.

That curiosity and our curious skillsets and tools can allow us to revisit and look anew at many of the received stories we have from our past. As I mentioned in the last issue, I started Eric White’s Johannes Gutenberg: A Biography in Books, and in the introduction he talks about exactly this situation [emphasis mine]: “A new assessment of his historical legacy that is skeptical of the stories that have always been told and is based squarely on the evidence of the surviving books attempts to get at what Gutenberg most likely did and did not do, and to clarify that while he exerted immense influence within fifteenth-century Europe (printing in Asia is another story), his ingenious work can only have influenced subsequent advances of liberty, science, thought, and world literature indirectly.”2

RK: I’m sure (um, I hope) that I’m not the only one who has the disturbingly frequent experience of thinking I’m almost done cataloging a book, but then finding one little thread untucked… that when followed, unravels the whole thing. First editions turn out to be unrecognized second editions. The 35 volume set you just collated and paid for turns out to be a contemporary deceptive forgery (I still have PTSD from that one). The attributed author turns out to be impossible. When you look closely, it’s just not what you originally thought. It’s the curiosity that saves you, of course—that one little clue you follow to its ultimate conclusion. Sometimes, however, it does feel like curiosity is the thing that doomed you.

At our office, we have a joke about when this happens: “you know too much about the book!” Everything is easier and simpler when you don’t know too much, of course. But the whole point of doing what we do, I suspect, is that we like getting into this situation (of course, it’s better when you figure it out up front. I’m still working on that part.). I got started down the garden path to bibliography by asking “how did Greek and Latin literature get to me?” This led to a series of other questions which now has my nose semi-permanently in Hoffmann’s Bibliographisches lexikon der gesammten litteratur der Griechen.3

There is a Latin aphorism taken from Horace, sapere aude — “dare to know.” Melanchthon took it as a motto when reforming the curriculum at the University of Wittenberg and Kant made it a tenet of the Enlightenment. I think it gets at how chasing after that sense of curiosity CAN be a little bit scary. You don’t always know where it is going to take you. If you just want to get really good at something and only do that, I feel like rare books is not the best field for you. The fun part, for me at least, is that I’m always learning something new and finding my way into something I never expected (for example, last week: Old English homiletics!). However, what comes with that is always feeling like a beginner, risking being wrong, totally upending your own worldview about things, and generally cultivating an almost Lovecraftian sense of the vast “ungrasp-ability” of the world of knowledge (or maybe that really is just me). The more you build your own little fortress of expertise, the bigger the rest of the map of “terra incognita” reveals itself to be. Curiosity is necessary to survival.

Two Cool Things

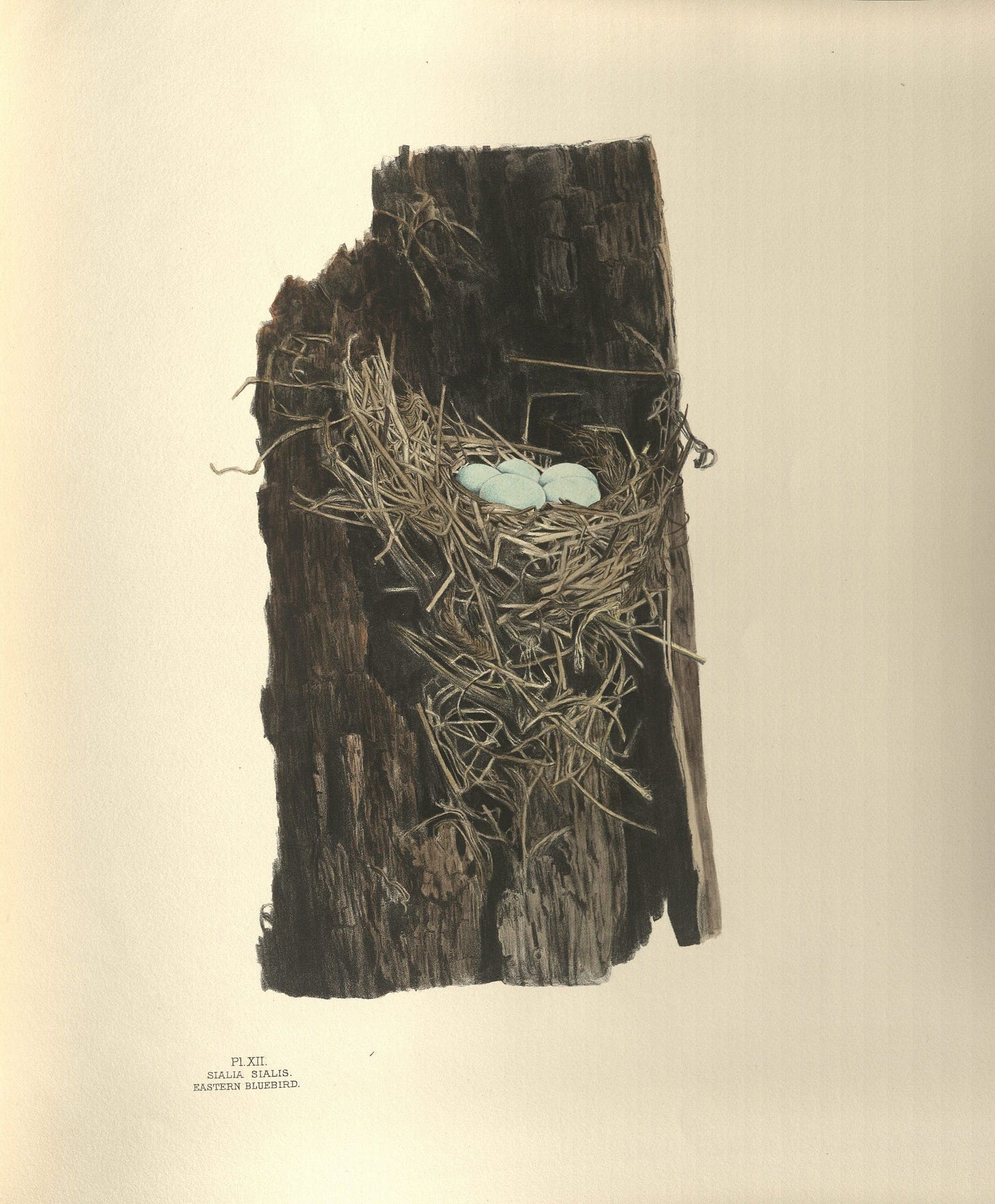

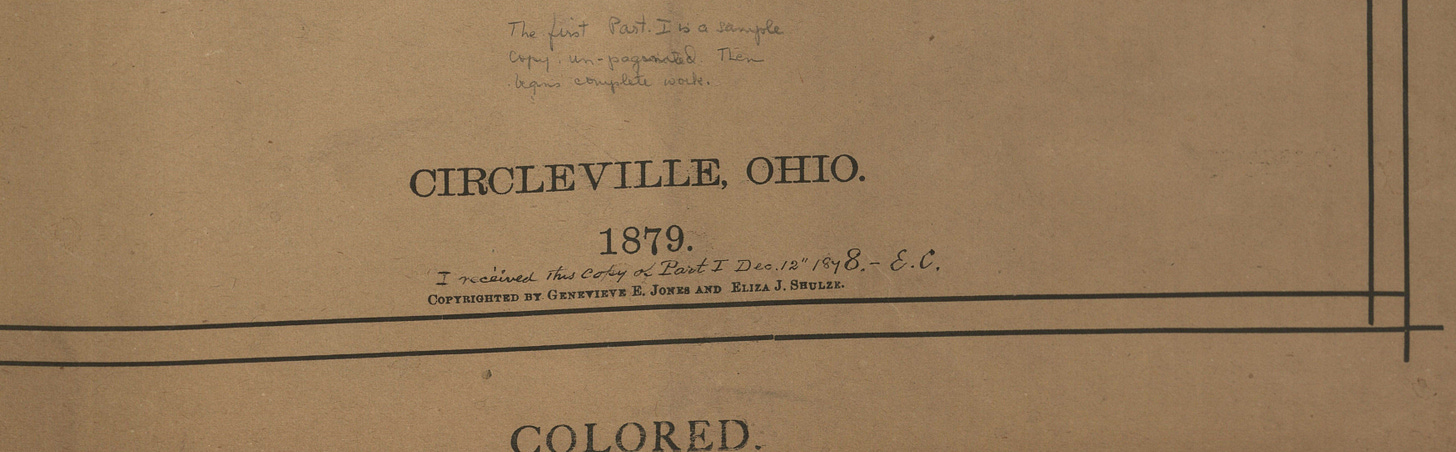

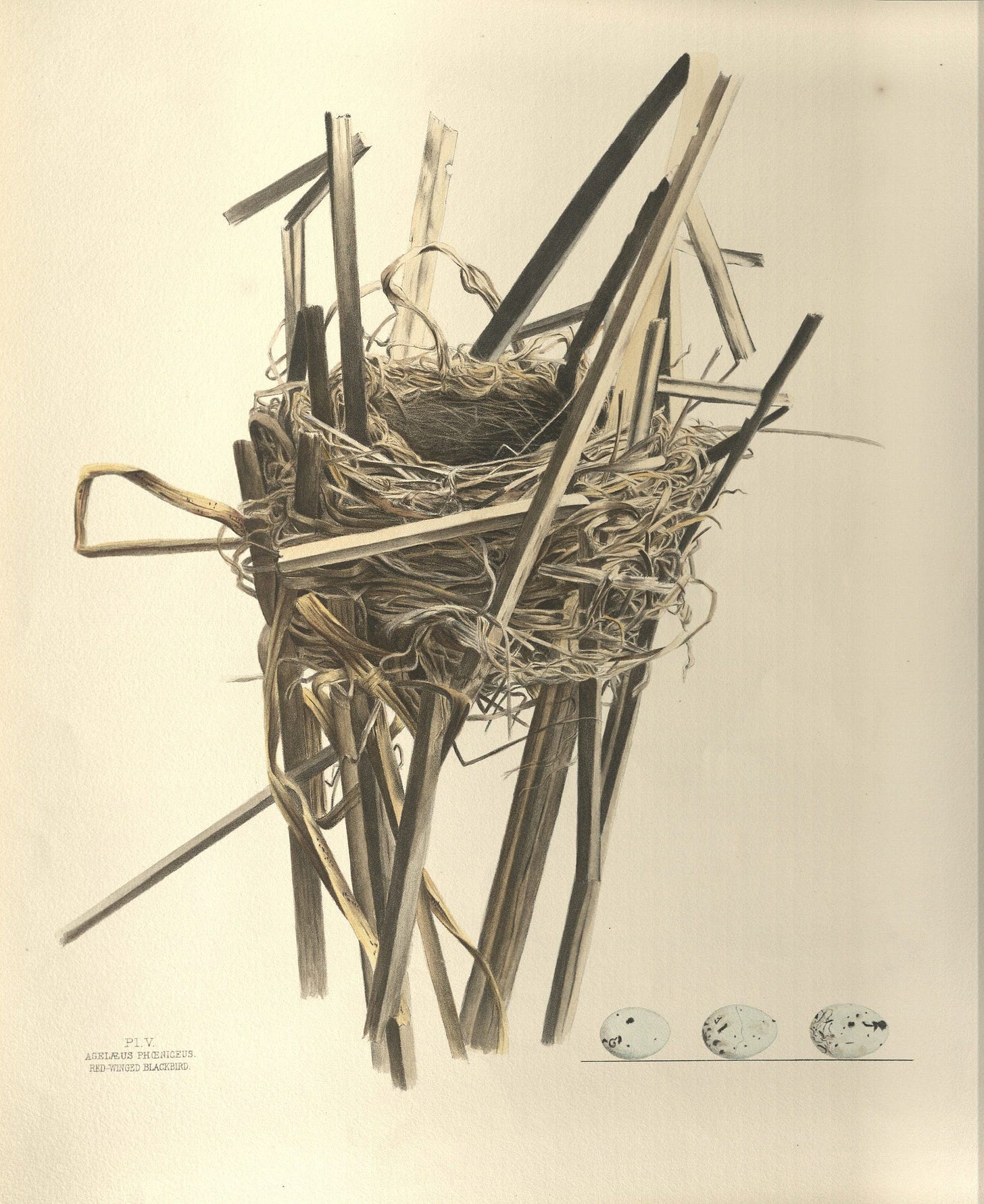

JWD: Early in my career, while at Crystal Bridges, I cataloged a copy of Genevieve Jones’ Nests and Eggs of the Birds of Ohio, a project very much begun as a result of curiosity. As was my practice, I pulled up Bill’s entry for the book in ProCite and read his notes, which in turn referenced the late Joy Kiser4 on the work of the Jones family and this arresting book. The notes describing the circumstances of the books production were compelling, and increased my fascination with it.

In brief, Genevieve saw Audubon’s paintings of birds of North America in the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. She noted that the nests and eggs of the birds were absent from Audubon’s work. This rekindled in her an interest (ignited when a young child) in creating a book that described and illustrated those nests and eggs of bird species in North America. Her father, Nelson Jones, was a physician and remarked that he would support the work necessary for such a book. And so, with the backing of her family and friends (especially her childhood friend Eliza Jane Shulze), Genevieve began the work of drawing - and creating the lithographs for - this book in 1876. I am so happy that Spencer has a copy of the book, since there are so few surviving copies. It’s a testament to Genevieve’s curiosity, and her family’s love for her.

The lithographic process was a challenging one to learn for Genevieve, requiring the printer, Adolph Krebs, to make round trips from Cincinnati to Circleville to assist the family in their effort, and offer corrections. However, by 1878 enough plates and drawings were produced to create the first part (of 23) which served as a prospectus for the rest of the project. One of the copies of this first part was sent to the prominent ornithologist Elliot Coues, who remarked: “There has been nothing since Audubon in the way of pictorial illustrations of American Ornithology to compare with the present work - nothing to claim the union of an equal degree of artistic skill and scientific accuracy”. To my surprise, the Spencer Library has the very copy sent to Coues, as noted in his manuscript note on part 1:

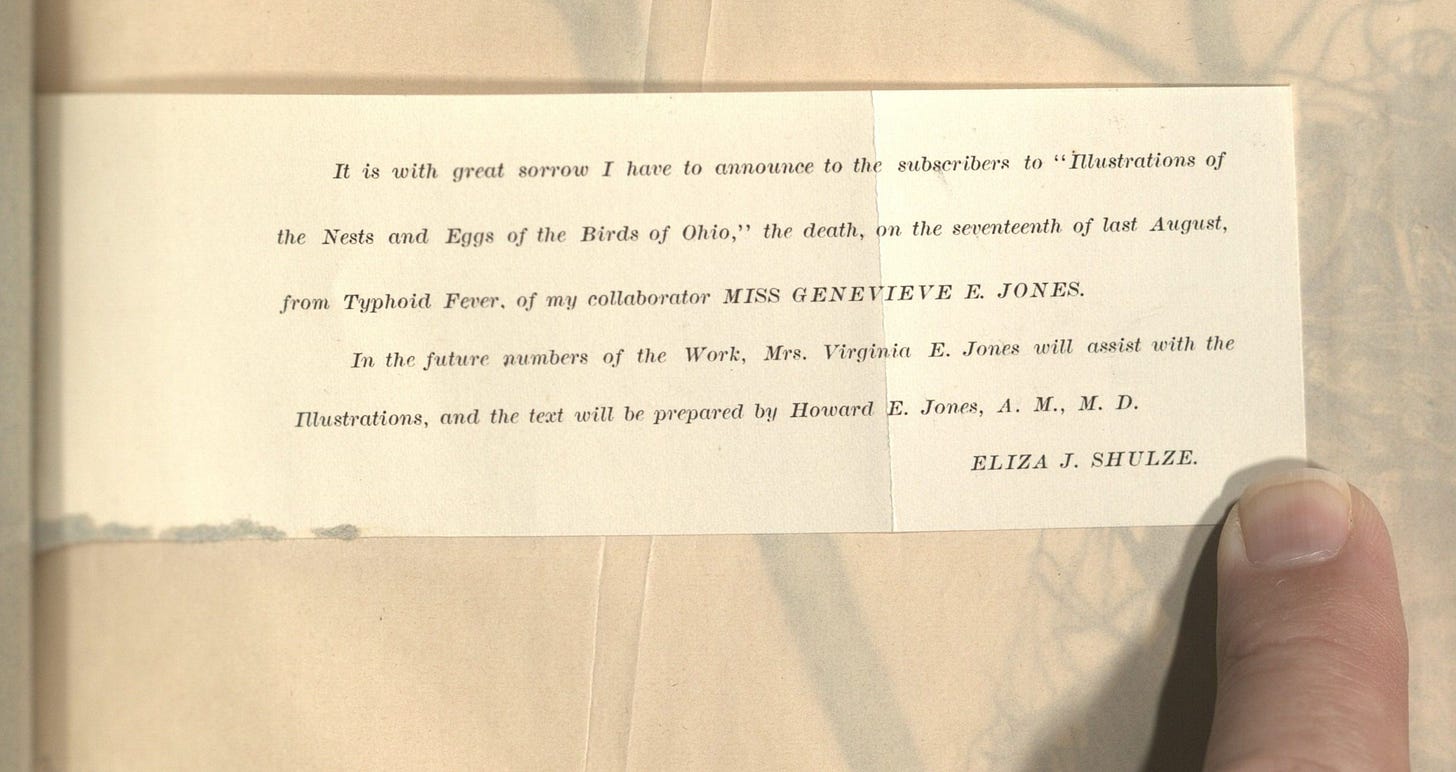

Coues’ praise helped boost subscriptions. Another American ornithologist, William Brewster, said of the book: “The Baltimore oriole [sic] seems to be almost if not quite faultless. The nest is exquisitely represented and the eggs are equal to if not superior to those given in any plates that I can now recall. The nest of the wood thrush [sic] is even more admirably delineated and is in its kind a perfect masterpiece. Please accept my best wishes for the future prosperous continuance of the work which is altogether too good to fail.” Coues’ and Brewster’s positive reviews led to additional subscriptions: President Rutherford B. Hayes and then Harvard college student Theodore Roosevelt. Work on the book continued until August of 1879, when Genevieve died suddenly of typhoid fever. A note was inserted in part 2, with Eliza announcing the death of her dear friend:

As you might well imagine, the family took stock of the project after her death. 15 drawings had been completed, well short of the over 100 illustrations intended for the book. Several weeks after Genevieve’s death, the family (and the wider community) agreed to see the project through to completion as a memorial to Genevieve. The family aimed to complete 100 copies of the book, which ran to 23 numbers. They enlisted the help of friends, neighbors, and also hired colorists to complete the book. Genevieve’s older brother, Howard, tried to assert increasing authority over the project.

It’s a very large book5, and Spencer (as I mentioned above) is extremely fortunate to have a copy. It was one of those things I hoped we might be able to acquire at my former workplace, but these are very rare in the market. I cannot locate a census of copies, but Kiser states that “Of the proposed 100 copies produced, fewer than half have been located in libraries and private hands.” The books are illustrated with handcolored lithographs, here’s a sampling from the Spencer copy:

A very rare book, born from extreme curiosity, that also has a tragic and lovely story attached to it.

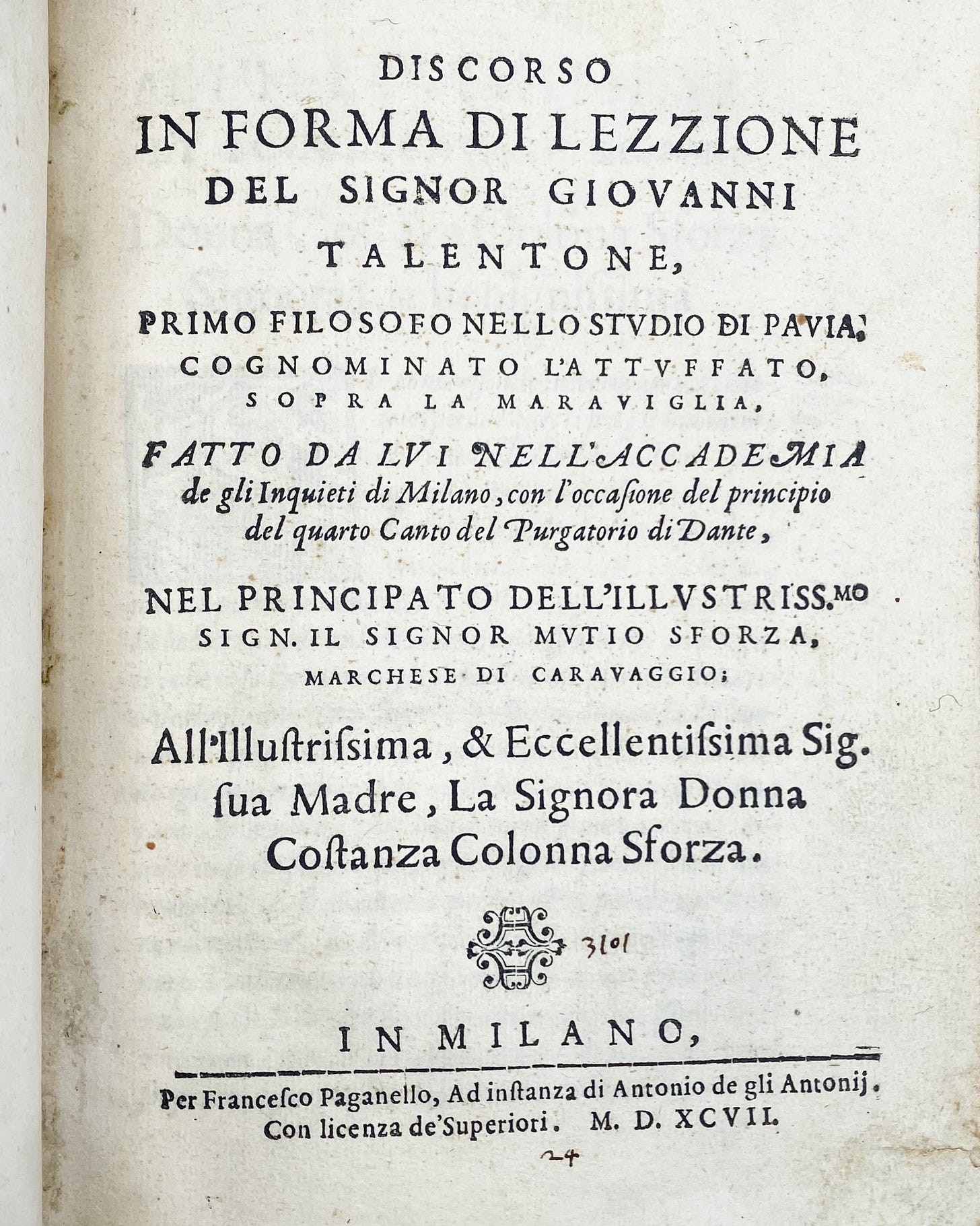

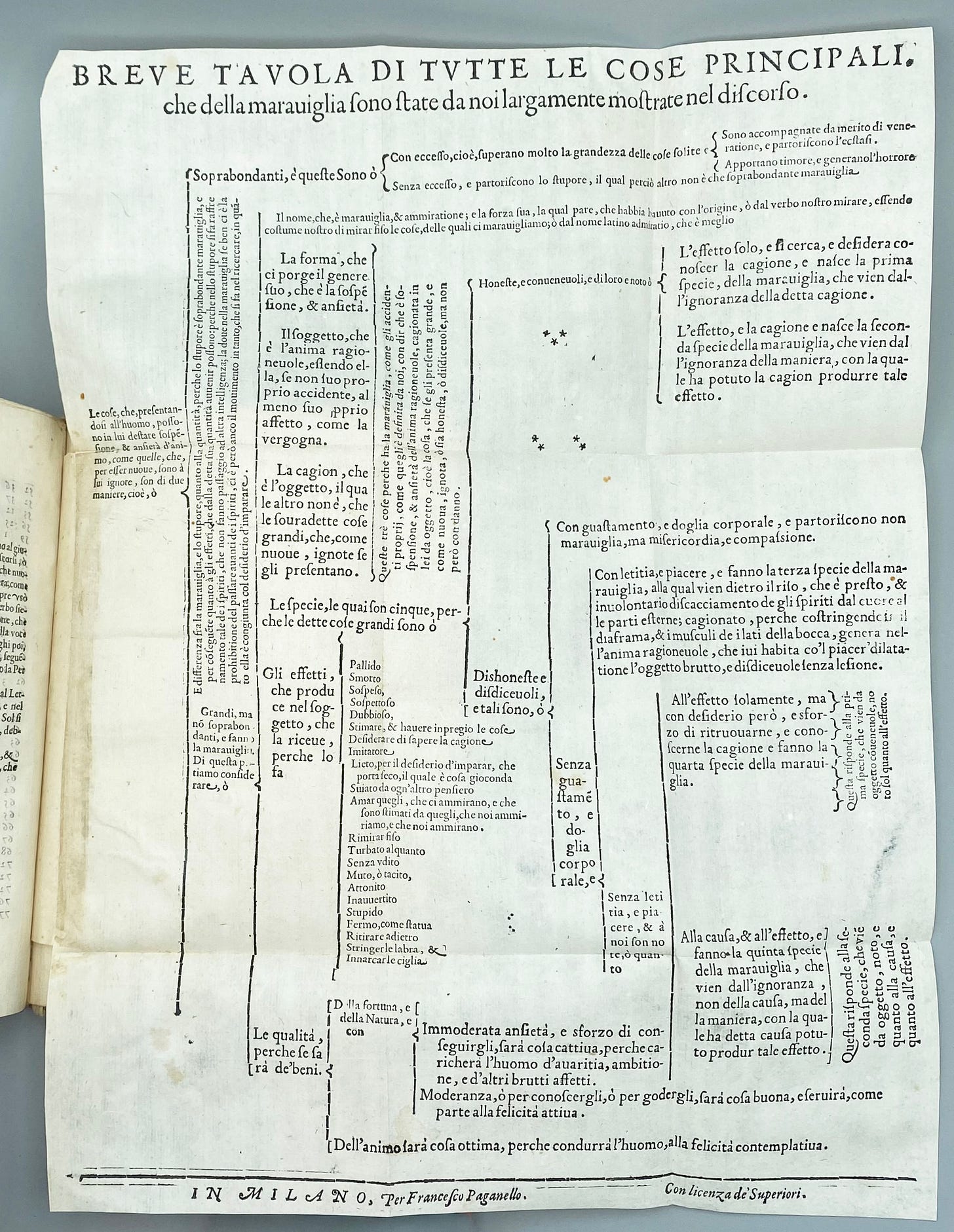

RK: This topic couldn’t have come at a better time for me, because I recently cataloged a very charming late sixteenth-century treatise on Maraviglia—the concept of wonder itself.

Giovanni Talentoni originally delivered this “Lesson” on wonder to the Accademia degli Inquiti in Milan in the guise of a series of lectures on Dante’s Purgatorio. From a few lines of poetry, he spins an argument for the essential goodness and importance of wonder—disagreeing in some places with Thomas Aquinas (Talentoni says that since Aquinas didn’t know Greek, it is understandable that he made a few mistakes!). Curiosity has sometimes been seen as a vice—distracting us from what is actually important and driven by sometimes prurient impulses.

For Talentoni, building on Aristotle, marvel is a passion which dominates the soul and drives it to discover the causes of things that inspire wonder. Thus, it is the root of all philosophical inquiry. Using poetry, philosophy, and science, he explores curiosity as an expression of the relationship between the world and the mind. In this printed version of his talk, he includes a “brief” schematic chart expressing his ideas!

According to the scholar Federico Schneider, Talentoni’s discourse influenced Claudio Monteverdi and the dramaturgy of his early opera, L’Orfeo—a distinctly marvelous work full of Dantean resonances.6 You can never predict where curiosity may lead you!

Current Events + Personal News

JWD: Mine and Adrienne’s blog post on the Spencer Library’s Hinman Collator (unsure how to properly capitalize that) is up and out and about! Here’s a link to it, and we’ll do a second segment in the spring.

Friend of the newsletter, Lucretia Baskin, shared this really lovely blog post about book curses by Kait Astrella: Curses Recast: Finding and Cataloging Book Curses at the Morgan Library & Museum. Very well sourced, illustrated, explored - and it’s by a cataloger! If you haven’t read it already, it’s very much worth reading.

Speaking of reading (wow that’s a bad segue for the newsletter), I had a chance to look through the Christie’s sale of Jay Pasachoff’s books recently, and I was pleased to see folks using mine and Nick Wildings’ work on il Saggiatore for exactly the purposes we hoped it would be put to. Here’s the lot - il Saggiatore, ex Pasachoff, and I think that by the time this issue lands in your inbox that the sale will be over, and so I hope some of you all got some of Jay’s books.

January 21 saw the livestreamed Pforzheimer lecture from the Ransom Center - featuring Ann Blair talking about the sizes of renaissance books. I assumed (incorrectly) that we’d be talking about the choice of format - i.e. folio, duodecimo, etc. Instead, she focused on ways that printers and writers worked to get their printed works to sufficient length - combining old with new works, related works, etc, so that an “appropriately” large book would be on the market. She gave two good examples in Gessner (printed by Gessner) and Erasmus (printed by Froben).

Finally, incredibly humbled to share here that on January 8th I was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, London. I suspect that many of the readers of this newsletter are partially responsible for this great honor, and I hope I can do that honor justice - and say an immense thank you!

RK: The Pasachoff books were the last thing I worked on before I left Christie’s—it’s was a bit wild to see it finally appear! Two years later, upon reflection, I might have reigned myself in a little bit on the Kepler descriptions. Then again, it was my last hurrah.

The McKittrick crew had a blast at Bibliography Week as usual, and for this year’s showcase put together a little e-list on bibliography and bibliophily. We’re now hard at work preparing catalogs in advance of upcoming book fairs, fighting the still quite high piles of snow everywhere on our way to the office every morning.

If you’re heading to San Francisco for the ABAA book fair later this month, be sure to attend Michele Cloonan’s talk on pioneering American antiquarian bookseller Alice Millard! I won’t be there, but you can visit some of my books at booth 214! My colleagues will also be in Southern California for Rare Books Pasadena, at booth 14 at the Raymond Theatre. I will be back home in my igloo, waiting for spring…

Conclusion

RK: As always, thank you for reading and thinking with us! We’ll see you again next month… if not sooner!

From page 5 of his Descriptive Bibliography.

Eric M. White, Johannes Gutenberg: A Biography in Books. Reaktion, 2025, p. 7-8.

Seriously, I use it so often that my boss gave me my own copy so I would stop hoarding the main reference library one…

Joy Kiser, America’s Other Audubon. Princeton Architectural Press, 2012.

It’s so big it really doesn’t fit on the Spencer scanner. So if the images are a but substandard, that’s why.

For more on this, see Schneider, Unsuspected Competitive Contexts in Early Opera, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2016.