RK: Happy new year! Jason, thanks for encouraging me to address this topic. What began for me in 2018 as idle speculation about the career of the author of an article in Colophon has morphed into something of an ongoing research project on women in the mid-century rare book world—as well as a small but growing personal collection of their publications. The first fruit of this appeared in 2022: an article for the FABS journal on Lucy Eugenia Osborne, the first Chapin librarian. The work continues, in my spare moments (and sometimes by accident), and earlier this year I spoke to the Zamorano club on the role of women in promoting the study and collecting of Renaissance books in America.

I freely admit that I am, in general, primarily only interested in things which happened before the year 1650. But the history of the fields in which I work, bookselling and bibliography, feels increasingly vital to me. The pursuit of knowledge about the people I’ve come to think of as my “foremothers” has led me to new and unexpected places (archival research! collecting periodicals! oral history!) and I’ve discovered a lot which has surprised me: women pioneering the teaching of undergraduates with rare materials in the 1930s, exploring the origins of print (and paper!) in China, strategically promoting the collecting of early printing, and all manner of interesting bibliographic activities. While certain figures have achieved a level of mainstream recognition, there is a real richness of women’s intellectual community and achievement from this period that I don’t feel is often adequately recognized.

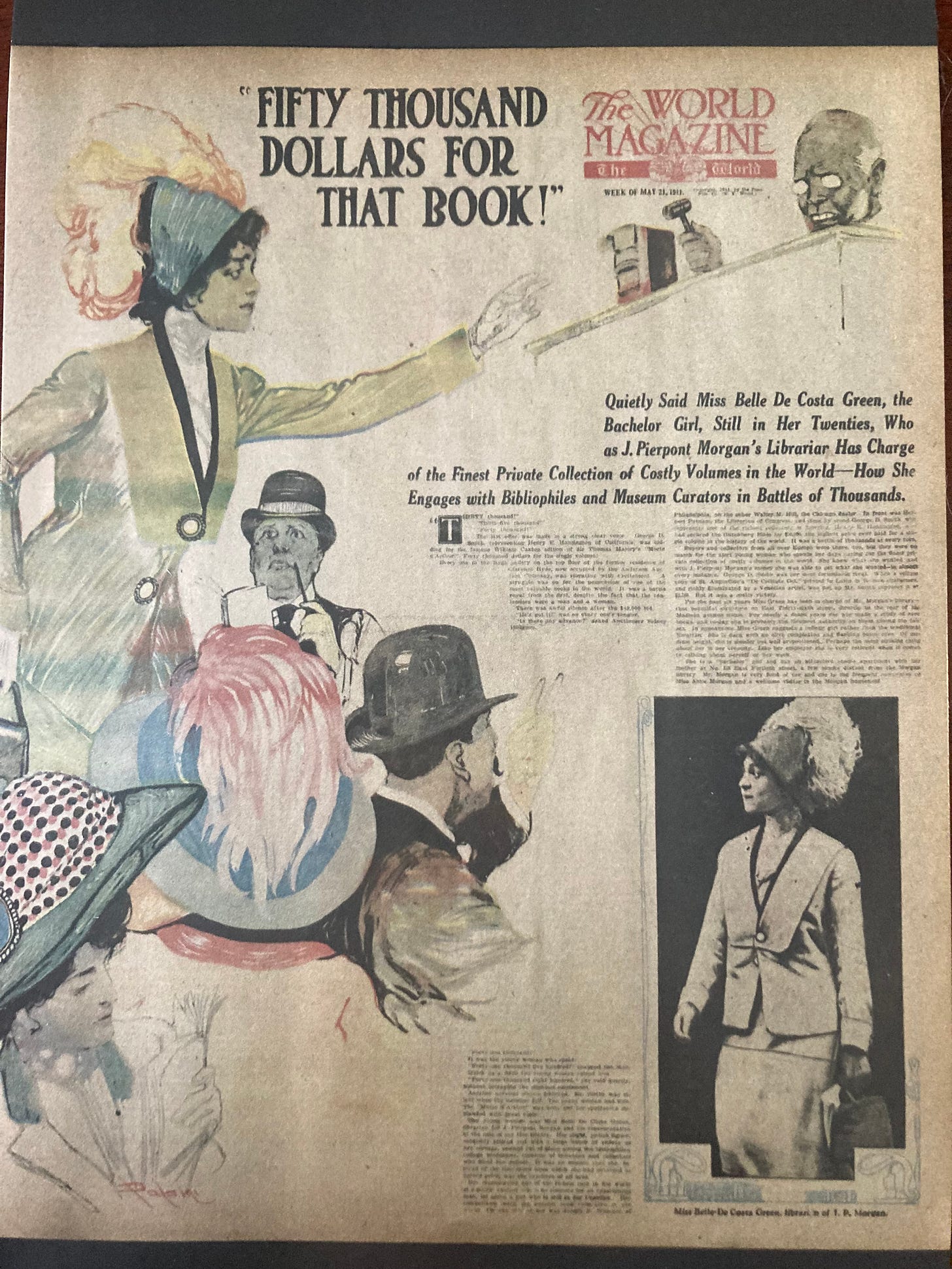

This seemed like an appropriate time to do a newsletter about bookwomen as the Morgan Library currently has on exhibit their long-awaited show about that most famous and fabulous of mid-century women experts in early books: Belle da Costa Greene. The New Yorker ran an insightful review of the exhibition, but I was surprised to see the author describe Greene as “one of few women with clout in the rare-book world.” I thought an impressive aspect of the exhibition was the degree to which it revealed the larger community, including many women, in which Greene worked.

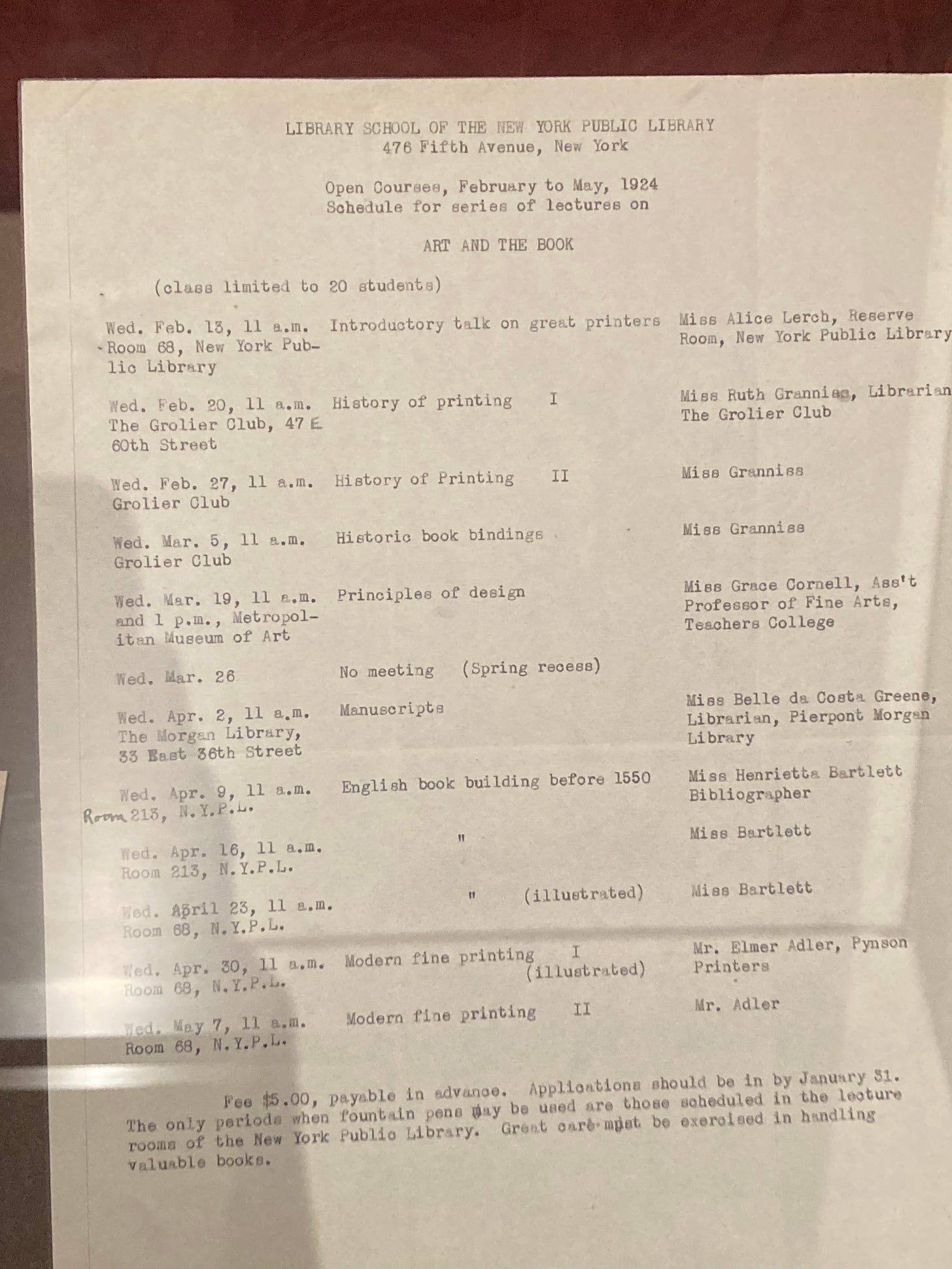

Greene was a uniquely distinguished woman in charge of a uniquely rich collection, as the exhibition makes clear. But she was not unique in being a respected woman in the world of rare books. While Greene was at the Morgan, Lucy Eugenia Osborne was heading up the Chapin as its first librarian (and one of her students, William Jackson, would go on to be founding librarian at Harvard’s Houghton library), Ruth Granniss was the librarian of the Grolier Club, and Margaret Stillwell was the curator of the Annmary Brown library now at Brown University (and was soon to become Brown’s first woman professor). The syllabus pictured above reveals the teachers for an NYPL course on book history, only one of whom is a man (and he’s talking about modern printers!). The exhibition also highlights Greene’s role as a mentor to other accomplished women scholars and librarians: Ada Thurston, Meta Harrsen, Dorothy Miner, and Edith Posada to name only a few. There is a whole section on Black women librarians (a complicated intersection with the life and career of Greene, who passed as white—something the show and catalogue also sensitively explore).

JWD: I cannot tell you how many times, Rhiannon, I’ve consulted Stillwell’s Awakening Interest in Science, especially as we investigate and talk about the scientific incunabula at LHL. I think another connection that strikes me is that much like science, in the field of bibliography - women have always been “there” doing outstanding work for less compensation and notice than their male peers. But it is still important work. Indeed, from my side of the rare books boulevard, librarianship continues to be a “feminized” profession. Much of the work that we do is grounded in important work done by women (and also LGBTQ folks)!

I do think that there’s a parallel here between describing books and bookwomen - it’s in what we share, what we talk about, and what we tell. The work is there, we just need to talk about it.

RK: I bristle somewhat at references to women working and writing in this field as somehow being “hidden voices.” Their names are on the title pages! They are in the acknowledgments. They were professionally accomplished in an international community. They are right there. But for some reason, the stories we choose to tell often exclude them—even in the face of copious evidence to the contrary. The narrative of one or two exceptional exceptions seems to constantly win out. Whether trying to create a false image of “good old days” to hark back to or indeed of “bad old days” which we, in our enlightened modernism, have corrected, it does a real disservice to the legacies of the women who helped build the field. I really enjoyed the Morgan’s presentation of Greene as part of a larger community of both men and women, and I hope to see more treatments like it.

Margaret Stillwell’s autobiography, Librarians are Human, presents bibliography as what she calls as “gentleman’s world” to distinguish between the absolutely terrible and ungentlemanly way she was treated by the faculty at Brown when she became a professor. But it was gentleman’s world which, in her telling, was nevertheless populated with brilliant, funny women working together and making bibliographic knowledge—despite all the professional and legal hurdles women faced.

Two Cool Things

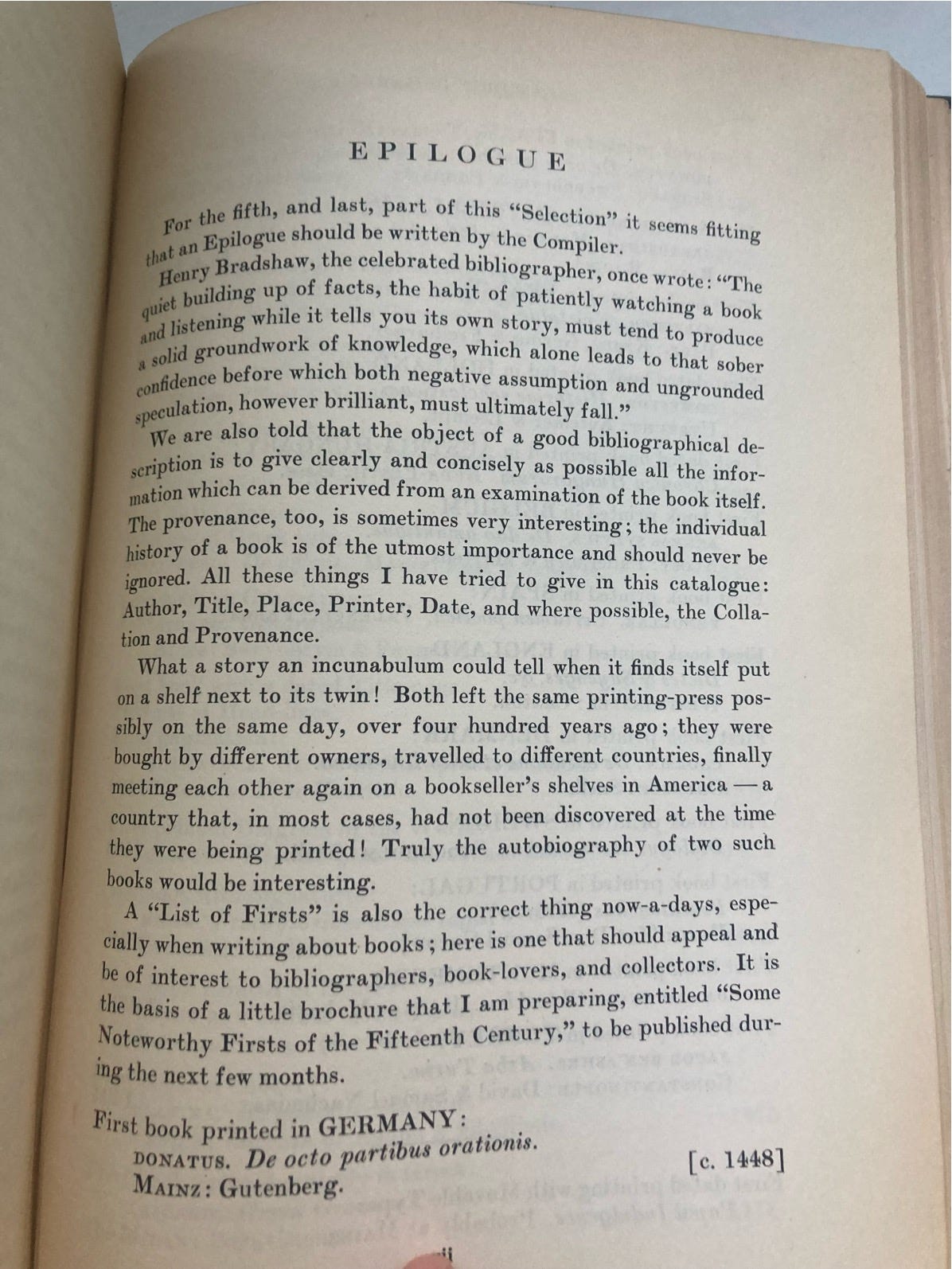

RK: A few years ago, I bought a copy of Lathrop Harper’s 1930 catalogue, A Selection of Incunabula Describing One Thousand Books Printed in the XVth Century.1 This was the first American bookseller’s catalogue devoted entirely to pre-1501 imprints. Each part after the first (it was issued in five) has introductory remarks by a different luminary of the field: Lawrence C. Wroth, Margaret Stillwell, Lucy Eugenia Osborne, and George Parker Winship. Leaving aside the implications that half of these contributors, in the years around 1930, were women—what most excited me about the book was the discovery that there is an epilogue at the very end by a person announcing herself as the compiler of the catalogue: Emma Miriam Lone.

I had no idea who Emma Miriam Lone was. But it turns out she was not only the cataloguer of the first American bookseller’s catalogue of incunabula, she was Lathrop Harper’s—the pre-eminent American book dealer at the time—cataloger for over 30 years! She is actually one of only three women mentioned in Winslow Webber’s 1937 Books about Books: A Bio-Bibliography for Collectors. So why, whenever I ask knowledgable people in the New York book world, has nobody heard of her?

I have, however, begun to discover answers to the question “who was Emma Miriam Lone?” From a Columbia University oral history interview with Douglas Parsonage, who also worked for Lathrop Harper for many years, I learned that she was… his aunt! According to him, she was apprenticed to a bookbinder a young age and actually worked for Kelly’s, the outfit that bound trade editions of Dickens and Thackeray. After some time working for a print dealer and the Women’s Book Workers guild, Emma sailed from England to the US in 1916, right in the midst of WWI. She had no letters of introduction but got a job with the dealer Mack Hartwell. Only a few years later, she offered to watch Lathrop Harper’s shop while he was away in Europe for his annual buying trip. Harper told her to make herself useful while he was gone, and she apparently just started cataloging books… and then kept doing it for the next three decades. When Emma’s sister came to New York to be her housekeeper, she got Douglas a job at the firm.

Her single book-length publication, A Few Notable Firsts in Europe during the Fifteenth Century, is an expansion of her remarks in the epilogue of the 1000 Incunabula catalogue. In correspondence with Leonard Mackall held by Johns Hopkins, she writes that she hopes “it will do something towards promoting an interest in fifteenth-century books in this country.”2

To the 1932 issue 11 of The Colophon (whose editors included, by the way, Ruth Granniss and Belle da Costa Greene…), she contributed a remarkable essay entitled “Some Bookwomen of the Fifteenth Century.” In it, she expresses about the 15th century many of the same sentiments I have just now shared about the 20th: that there have always been women out there, doing the work—if only you care to look.

Rather wildly, she closes by claiming that the first bibliophile in recorded history was the 10th-century nun Hroswitha, and makes the following proposition:

When our lady booklovers have grown sufficiently numerous to form a “Hroswitha Club” in honor of the founder of bibliophilism they will have an interesting field to explore in connection with this nun’s life and work. These few women are the most outstanding—bibliographically—of the fifteenth century. Of course there are many Lives, Memoirs, etc. of female saints, such as Brigitta, Ursula, Catherine, and others, written or published in the fifteenth century, just as there is a long and distinguished list of patronesses without whose sympathetic aid and encouragement many writers and printers would never have written or published some of their masterpieces. The latter’s contribution to literature is no less great for being in such an intangible form, and there are so many of the former, or relative degrees of importance, that it would need more space than than is justified in this article to deal with them adequately.

The all-women’s Hroswitha Club, a counterpart to the Grolier Club which barred women members until 1976, was founded in 1944. Lone was not a member, but I can’t imagine that this article is not the initial inspiration for the club—and certainly for its name. Yet she has been largely forgotten, even as the club’s history has received additional attention in recent years.

This is where I make a plea: if you know anything about Emma Miriam Lone or have clues about where I might find caches of her papers, please let me know! I’m on the hunt, with the hopes of someday writing an article about her. And a second plea: if you have been working on your own bookwomen research projects, get in contact and tell me about them!

JWD: I’ve got Historia Coelestis brain, Rhiannon. (Reader, you’ll see why at the end). In the spirit of talking about the work of women and the making of books, I’d like to talk a bit about Margaret Flamsteed and her work on the creation and publication of the 1725 Historiæ coelestis Britannicæ. This book, which appeared in three volumes (and to my mind is only really complete with the Atlas Coelestis), appeared after John Flamsteed’s death, and was the work of his widow - Margaret - and Flamsteed’s assistants, Joseph Crosthwait and Abraham Sharp. The dedicatory preface (to George I) is signed by Margaret and Jacob Hodgson.

This book is one of the foundational datasets for the science of astronomy - and is the only large scale product of Flamsteed’s work as the first Astronomer Royal. In it, Flamsteed reprints the star catalogs of Tycho and Ptolemy, and for the first time, produces highly accurate (and corrected) positions for the stars, planets, and the moon. He and Johannes Hevelius argued about the merits of instrumented vs naked eye obersving - but that’s a whole other thing. After Flamsteed’s death in 1719, Margaret was his executrix, and saw to it that these three volumes and the atlas were published, according to her husband’s wishes. She spent her own income, and devoted much of her time, to ensuring its appearance. Take, for example, her correspondence with the Treasury, in which she asks for the remaining copies in the Treasury to be returned to her, and the Treasure proposed3 to swap 39 copes in her possession of the corrected 1725 edition with the suppressed 1712 edition (which was riddled with errors, thanks to the haste of Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley):

His Majesty in the year 1715 bestowed on petitioner's husband, Mr John Flamstead, his Majesty's Astronomer, 300 copies of the astronomical observations made by him, and comprised in a book entitled Historia Cœlestis…Mr Flamstead has since that time been at a very great expense in printing 340 copies of another part, to perfect the afore-mentioned book, without which the petitioner is of opinion it ought not to go abroad as a performance of her deceased husband: prays that the remaining thirty-nine copies now in the Treasury may be delivered to her.’4

It’s not just Margaret’s posthumous work that made the book appear - her income also went to support the acquisition of instruments for the observatory, which (though designed by Christopher Wren) was essentially an empty building when John was appointed. It took years and some sponsorship for the Flamsteeds to appropriately outfit the observatory with sextants and with a large mural arc - both equipped with telescopes and micrometers. (I adore that Margaret and Sharp and Crothswait took their instruments with them - much to the chagrin of the second Astronomer Royal, Edmund Halley).

At the core - one of the foundations of modern astronomy - Flamsteed’s star catalog - would not have been possible without Margaret Flamsteed - both the book and the instruments!

Anyhow, if you want to know more, attend the talk (see the Personal section), and I am thrilled to be cooking some writing up with Emma Louise Hill. Watch this space!

Current Events

RK: We have watched the news of the terrible fires in Los Angeles with great horror. Some of our dear readers in LA have suggested some charities to draw attention to, and so here are some places to consider giving if you can:

Here on the East coast, Bibliography Week is about to begin. The Bibliographical Society of America has a full slate of exciting events around New York and online; you can check it all out here.

JWD: In keeping with our theme, I have two items of note here - first that our friend and my former colleague, Jamie Cumby, is running for RBMS vice chair/chair elect! Jamie is an incredible person - and scholar and bookwoman! I am thrilled to see her running for the position, and hoping we can bring a little more “B” back to “RBMS”.

I also want to draw attention to the recent publication of Trevor Owens’ recent book, After Disruption, which is strongly recommended to me and to you. I really need to dig into it, but as someone who works in cultural heritage, it’s a deep look at our shared work after, well, the trends of disruption.

And finally (for me), I’m watching the sale of parts of Owen Gingerich’s library at Christie’s later this month. Owen was a bit of a sophisticator, and so his books (said with kindness) should be looked at closely. He didn’t really make a secret of this5, though, so I don’t feel like I am posthumously skewering him. Still, interested to see what happens with the sale.

Let’s Get Personal

RK: I’ll be in New York for Bibliography Week, so I hope if you are also you’ll come by the dealer showcase at L’Alliance and visit the Bruce McKittrick booth to say hi!

JWD: My colleague, Finch Collins, will also be at Bib Week - please say hello to him - it’s his first one!

My friend and colleague, Lynne Marie Thomas, asked me to give a virtual talk at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Super kind of her to ask, and after mulling a few things over, we settled on a talk about the 1712 edition of John Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis. I talked about this work with Adrian Johns previously in an After Hours, but am flying solo this time - except for really solid guidance from Emma Louise Hill (another incredible bookwoman), who likely knows more about Flamsteed’s printed works than anyone else on this earth. Anyhow, the talk is free and online, so please do attend! Here’s the link to register, etc.

I also had a lot of fun appearing with Finch Collins and Kim Masteller (from the Nelson-Atkins) to talk about our collaborative exhibit, Mapping the Heavens. It’s a really great show that we’re proud of, and it was so fun to be on KCUR, our local NPR station, to talk about it. Here is the link to our interview, and I hope you all can come and see the show in-person. If not, Finch created this great digital collection that assembles the 14 items we loaned for the show, as well as some great secondary resources.

Conclusion

The conclusion seems like the right place to acknowledge that Half Sheets is now one year old! Remember when? We might not hit an issue every month, but there are 8 (9, counting this one) issues out there, and I blush a bit at the warm reception our work here has gotten. We’ve got about 160 subscribers, and I am sure we’ll pick up more in 2025. Please do share the newsletter with folks that might be interested - it’s free and open to anyone.

It also seems like a good time for another special interview issue, coming soon. Keep an eye out for a “Bookwomen” related piece in coming weeks!

Until then, we wish all your quartos to be in fours, and your octavos in eights,

Rhiannon and Jason

It’s actually Howard Lehman Goodhart’s copy—the father of the collector and Renaissance scholar Phyllis Goodhart Gordan.

Many thanks to Dr. Martin Michalek for his assistance accessing these documents from the Leonard Mackall papers.

This was a small correction from the newsletter as sent - Emma Louis Hill pointed out my error here, thank you as ever, Emma!

'Volume 227: January 18-April 30, 1720', in Calendar of Treasury Papers, Volume 6, 1720-1728, ed. Joseph Redington (London, 1889), pp. 1-10. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-treasury-papers/vol6/pp1-10 [accessed 12 January 2025]

Take a look at the entry in Owen’s census for De Rev for his own copy of the 1566 edition for an example.

Such a wonderful newsletter, I’ll be sharing with my library patrons! There’s been a ton of interest in the new Morgan exhibit from them and I’m excited to hear more discoveries about Lone that you may find.

Fascinating. Book and publishing history isn't my area, but I have found in reading my 17th and 18th century French sources that professional women in various fields are mentioned. As you say, it is unfortunately the case that their existence has been overlooked by subsequent generations.