Theme

RK: Hello! Welcome to the new year. And thank you for subscribing to our newsletter, in which we are discussing the fine and occasionally controversial art of annotation. Jason, do you write in your own books?

JWD: Rhiannon, you’re starting off with what is very much a big point of contention with bibliophiles, and readers generally! I abhor writing in my own books. I wonder if this comes as a reaction from my youth in a very conservative Christian church, where annotation almost seemed to be a competition - who could highlight, underline, and marginal note more than the other person. I’m not above adding a bookplate to my books, but no, I just cannot bring myself to write in my books. I do make pseudo commonplace books in google docs for books with a lot of good quotes (looking at you, Manguel’s Library at Night).

Now articles I print out get covered in annotations, but I suppose I feel like those are somehow more ephemeral.

But it’s not just about our own annotation habits, is it - since we both work with books with annotations by prior readers? Those sorts of book tend to be of much greater interest now, to the posthumous chagrin of my predecessors at Linda Hall, who sought “clean” copies of books.

RK: Stephen Orgel writes about this really wonderfully in his monograph The Reader in the Book. He discusses how marking up your books was once considered an essential part of reading. What else is all that lovely white space in the margins for??

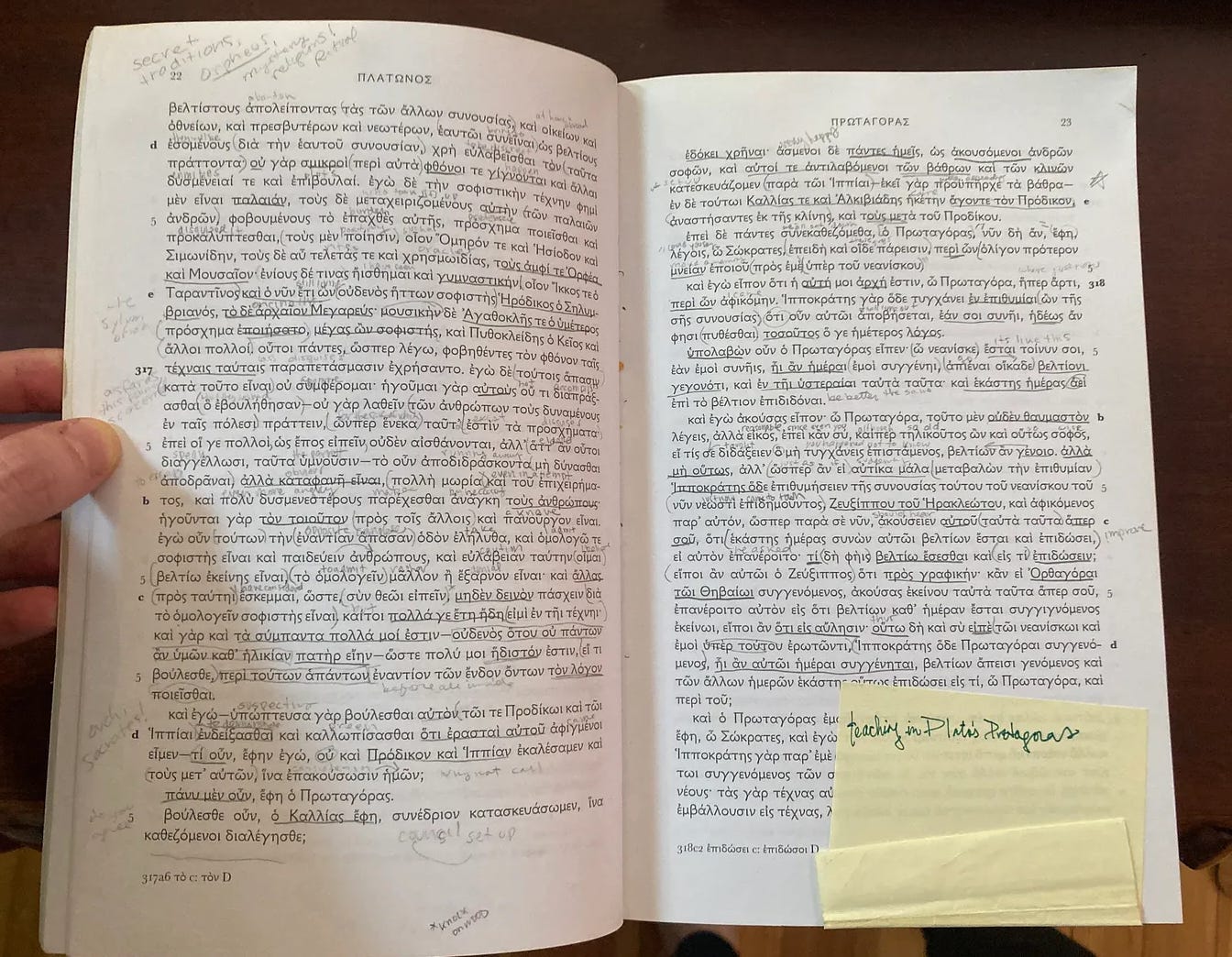

As you can see, I’m very guilty of writing in my books. As a student of languages, I found marking a really essential way to process as I read and translated (and of course, to help me recreate it when called on in class!). When I started working with early modern books later in my career, I was so charmed to see that many school texts of the authors I read in college and graduate school were marked up similarly.

The printed book can give an illusion of finality and uniformity, but of course as we know, every copy of a printed book is still unique. As Orgel writes, “Books are not absolutely dead things.” They have long lives, and their readers (and their marks) are part of those lives.

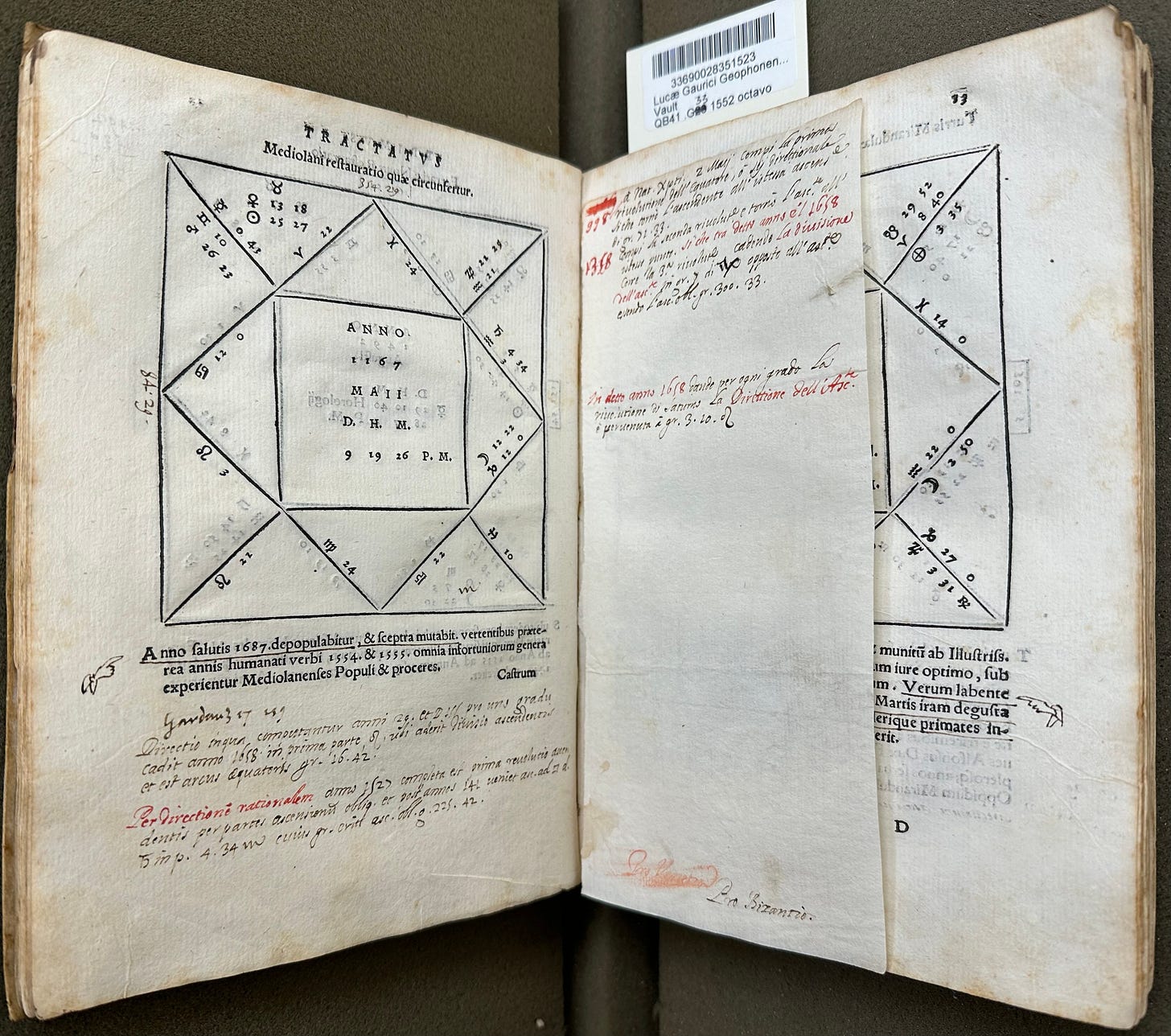

JWD: A recent acquisition I made for LHL at the Boston Book Fair was a heavily annotated copy of Luca Gaurico’s Geophonensis episcopi Ciuitatensis of 1552. Sara Trevisan of Sokol pointed it out to me, and it was an instant “yes.” First, we didn’t have a copy of this title in the collection, and this is at a time when astrology and astronomy were one and the same.1 Second, those extensive annotations! Those annotations, as my colleague Finch Collins traced, are in at least two hands, one by Spinola and the other by Oderico, who were friends. Interesting to speculate on if the book was shared among them and they built on each other’s annotations.

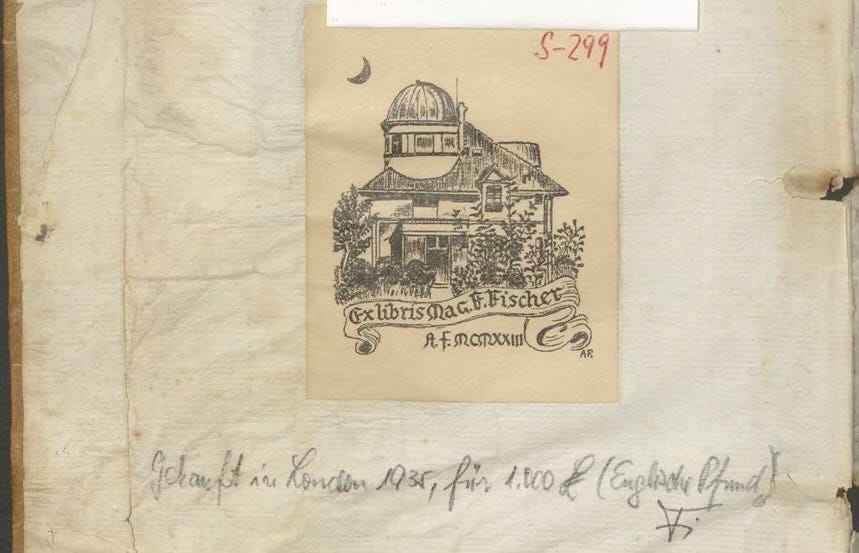

One aspect that occurs to me as we work on this issue is how frequently dealers, former owners, or other librarians add notes in on either the front pastedown, or the front free endpaper. This is both great and confounding - because it’s another “thing” to have to check when you describe a book! Maybe the most fun example of this for me was the note by František Fischer on the front pastedown of what is now LHL’s copy of Giulio La Galla’s De phoenomenis in orbe lvnæ novi telescopii vsv a D. Gallileo Gallileo, where he notes “Gekauft im London 1935, für 1.000£ (English Pfund)

Fi. [Purchased in London 1935, for £1,000 (English Pounds) Fi[scher]].

But that’s just a price note, the wild stuff comes in when someone engages in a bibliographical description at the front of the book, or adds a note in that they think might be helpful, like in our Aristotle Opere, printed by Aldus between 1495 and 1498.

RK: I LOVE bibliographic marginalia, which I think might deserve its own issue. Sometimes you feel like the book dealers and catalogers of the past are passing you a secret helpful message. Other times… well, let’s just say I hold to Umberto Eco’s dictum: “books are not made to be believed, but to be subject to inquiry.”

It is really wild that bibliophilia went through a phase of preferring “clean copies,” (um, let’s be real, at the same time a lot of these notes were being added to flyleaves and pastedowns!!) to the point of washing and trimming away marginalia. And this is still to some degree true I think in the market for modern first editions, although even that is changing, with an increasing preference for important associations and inscribed copies. I am so glad there is a growing appreciation for the value that annotations give books, both in scholarship and in the market. Last year, Quaritch released a truly lovely catalogue of annotated books which celebrates what they called in their email about it (which I can’t find now, so I’m paraphrasing) “the polyphony of voices” present in such books.

JWD: That Quaritch catalog got a lot of good buzz, which was well-deserved. We bought two of the items from it - no. 24 (Pomponius Mela, [O]rbis situm dicere aggredior impeditu[m] opus & facundiae minime capax, 1477, with a CHARMING almost shopping list in Latin), and no. 45 (Sphaerae atque astrorum coelestium ratio, natura & motus, 1536, with extensive marginalia and a really nice “auctore damnatus” note) Maybe the most well-known example of the importance of annotations was the late Owen Gingerich’s lifelong work on existing copies of Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus, popularly shared in his The Book Nobody Read and examined in a scholarly light in his An Annotated Census of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus. Gingerich, rightly, objected to the popular assertion by Arthur Koestler (in the charming Sleepwalkers) that no one read De Rev. Well, Gingerich conclusively discounted this argument thanks to - you guessed it - annotations. In the process, he uncovered some incredibly significant copies of the book, including the one annotated by Johannes Kepler.2 Gingerich’s work has been contorted in numerous ways (some of which I’ve co-written about), but his use of annotations and marginalia in his work lays out, in big neon letters, the scholarly/academic/research value of annotations in early modern books.

RK: There is similarly enlightening analysis of the annotations in the first two editions of Vesalius Fabrica in Dániel Margócsy’s (et al.) masterful census of that work; I think also about Benjamin Wardhaugh’s “Reading Euclid” project. In addition to the obvious benefits to our understanding of early modern reception that come from marginalia, however, I have recently been reflecting on what an intimacy it offers to us as readers now. Annotation can be a sort of a conversation between a reader and the text itself—albeit one to which we are outsiders, often missing part of the context. But for me, part of my whole attraction to the world of the Renaissance is reading people who were reading the same texts I know and love from my education. There is a way in which, when I am studying Marsilio Ficino or Tullia d’Aragona,3 for example, part of what we are doing is all reading Plato together. Annotation really brings this out for me; even if the writer is nameless and faceless to me, we are still reading together. There is a feeling of triangulation that reminds me of a poem by Sappho, her fragment 31:4

He seems to me equal to the gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you"

sits and listens close

to your sweet speaking5

Another way of looking at it, I guess, is like you are eavesdropping on someone else’s conversation. You can’t quite get it all, but it is still a special pleasure.

Two Cool Things

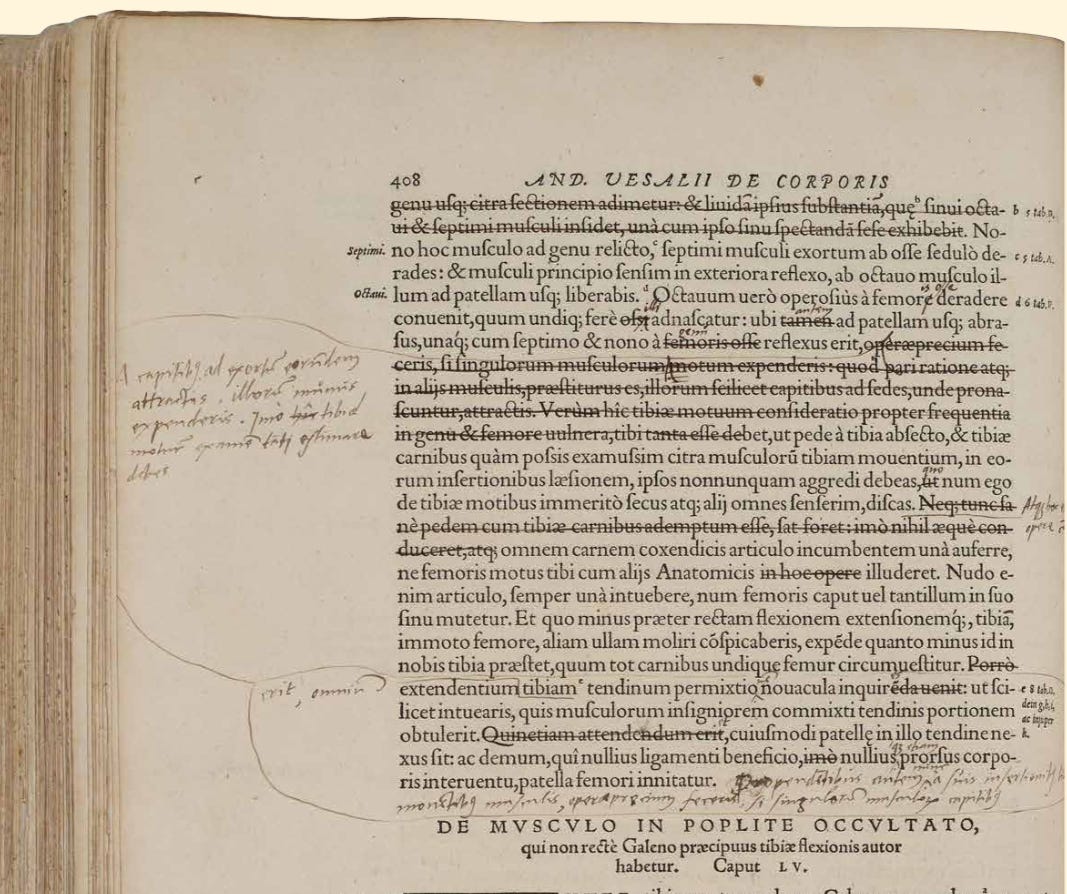

RK: One of the reasons annotation has been on my mind lately is because of a big project I’ve been working on: writing the catalogue for Vesalius’s own annotated copy of the second edition of the Fabrica, which we are offering for sale at the end of this month. It’s a really incredible book (with a crazy origin story to match)—one of those things that really makes you appreciate working at a place like Christie’s. It is a little bit different from most of what we’ve been discussing because it is an author annotating his own book. It comprises the proof sheets of the second edition which the printer, Oporinus, sent to Vesalius in the final stages of publication. Vesalius used them as the basis for planning the never-realized third edition of the Fabrica (he died tragically young while returning from Jerusalem).

Vivian Nutton, the scholar who confirmed the attribution of the annotations and a great authority on the history of medicine, mentioned to me that people are often surprised to hear that he felt confident that it was Vesalius almost immediately upon seeing it. Having spent a lot of time with the book over the last few months, I completely see where he is coming from: even if you can’t read the annotations, they are very clearly not reader’s notes. They are the kind of marks—deletions, edits, and moving things around—that only the original author would be interested in putting on the text.

I don’t think I need to go into all the reasons why this particular copy is so special (although if you want to know more, check out the catalogue!). But in the context of this newsletter, I wanted to pay attention to a few particular aspects of the annotations. The first is that many of them are minutely and almost obsessively concerned with correcting his own Latin prose style. Even over a decade after the publication of the first edition, Vesalius was thinking and rethinking the best way to express his ideas. Of course, Vesalius made quite a bit of his reputation (and perhaps also his infamy) by correcting errors in Galen; I found it so wonderful and almost moving to see that Vesalius applied the same zest for correction and improvement not just to the medical canon, but to himself. Some of my favorites are places where he slightly tones down mean things he previously said in print about Galen. I wonder if age provided him with a bit of perspective on that one; we’re all just doing our best! (Well you know… most of us.)

His notes really show the messy work of doing and sharing scholarship, something that gets erased on the nice clean printed page of a well-proofed edition! And what is scholarship, what is science really, but the ongoing process of correcting and annotating the work of our predecessors? This book represents that perfectly. Also, I must admit, I have a bit of a crush on Vesalius after spending two months immersed in his work.

JWD: I suspect a few readers of Two Sheets will be completely unsurprised about the book I picked for this issue on annotations - LHL’s fine paper issue Sidereus Nuncius, Venice, 1610. I picked this because I love the book, and second it’s maybe outside of the normal realm of annotations we’ve been talking about, but linked with the Vesalius edits you shared, Rhiannon.

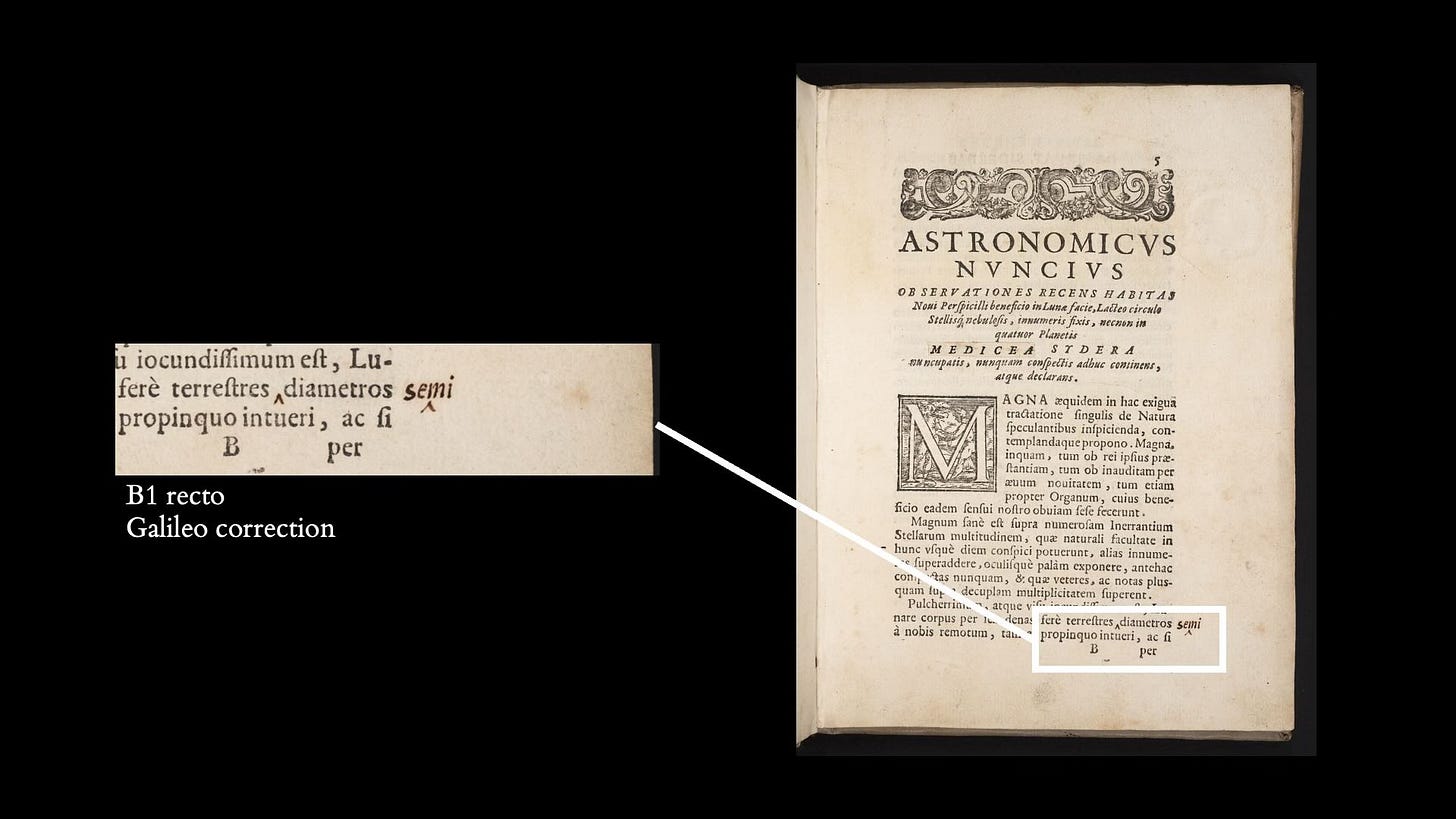

Galileo was an inveterate revisor and corrector of his printed works. I mean, just look at the bibliographical mess Galileo made of his il Saggiatore - which is very much the norm for him. And, to be fair, taking a manuscript and having it typeset and printed inevitably resulted in some errors. But, with the fine paper copies, Galileo had them in his possession, and these copies were gifts to the great and grand of “Italy,” which he very much wanted to present the best possible version of his work to.6 Thanks to Nick Wilding and Paul Needham (and me to a far smaller extent), we know that at least fifteen Galilean corrected copies of Sidereus exist, all with varying numbers of corrections - up to the seven in the copy at Brown (not JCB). The LHL fine paper copy has three corrections in Galileo’s hand, which corrected errors in his fair copy or errors that arose in the typesetting of the book. The first (and perhaps most glaring one) is the correction that appears on the recto of leaf B1, correcting Galileo’s own error in the distance of the moon from the earth.

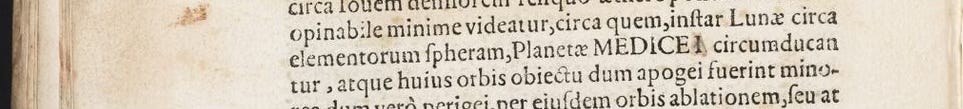

It bears remarking that Galileo used a specific hand that mimics the typeset text. Corrections in ordinary paper copies can be like this, or in Galileo’s more casual cursive hand. Regardless of the hand, the correction is pretty important, as that’s a 50% reduction in his calculated distance! The other correction that I should share is the one Galileo makes on the verso of leaf G4, correcting a grammatical error in Latin (see, Rhiannon, I can Do A Latin sometimes, but not like you [RK: frankly validating to see that Planeta, feminine in form but actually masculine gender, even tripped up Galileo!]) - “Planetæ” in Latin demands Medicei, not Medicea, and this Galileo corrects with a TINY cancel slip with his I correction in manuscript:

Isn’t that nifty, though? And it’s in keeping with the intense attention to typeface/hand, something seen in fine paper copies. If you want to know WAY MORE about the LHL fine paper Sidereus, I did a really fun program with Nick Wilding looking at the book, which you can watch here.

Current Events

JWD: It’s January, which means it’s time for Bib Week. (Note: wow, this looks a little light, is that all the public facing events? I know APHA has their meeting and there are a few other things as well?) I’m not sure if I am going (or if my velvet formalwear slippers can take another snowy dinner), but before we dive in, I understand you’ve got some fun stuff coming up in January, Rhiannon? And any highlights you have that you want to share?

RK: Yes! On January 17th, I’ll be talking with Oren Margolis, author of the first new monograph on Aldus Manutius in over 40 years, at the Grolier Club—it’s a live event, but it will be also be live-streamed. We are also having two public books exhibitions at Christie’s: our Americana sale, which includes a lot of very special documents as well as a fabulous collection of printed books on the history of New France. You can come see us January 12-16 in the main floor galleries at Rockefeller Center. Then from the 26th-31st, our online sale—including the aforementioned Vesalius—will be on exhibition upstairs, with lots of other history of science, as well as English literature, on view.

JWD: Well, for me there are two things (other than the annual Grolier dinner and meeting) that stand out - the first is H. George Fletcher’s lecture on the fine bindings held by the Club - I think it’s only available to GC members, though, unfortunately. This comes on the heels of the first sale of his collection, and is very much in George’s wheelhouse. I also think this lecture, Chinese Book Culture in Art-Historical Context, seems interesting to me, given my slowly evolving knowledge of Chinese/ east Asian books and book culture. I feel like bib week can be a bit of feast or famine for me - there’s lots of stuff happening, and some years I need to be everywhere all the time, and other years there’s not much of interest to me. I think this year is the latter.

RK: Bibliography Week is always very overstimulating for me, especially when I have sales going on at the same time. But I’d like to call out also the Bookseller Showcase at FIAF on Jan 22nd, always worth a visit. You will probably also see me around the Grolier Club quite a bit that week.

Let’s Get Personal

As you read this, Rhiannon is decompressing from the last auction year at a tree house-yoga hotel in Costa Rica, where she is hopefully seeing some sloths and actually relaxing.

And Jason is envious of Rhiannon getting to hang out with sloths. He just wrapped up a week in west Texas with family, taking photographs and he visited all (well, there’s only two) of the used bookstores of Lubbock, Texas - a community not known for its bibliophilia. He’s trying to get back up to speed at work, and deal with the perennial “let’s loop back to this in the new year” problem.

JWD: Maybe let’s conclude with a prompt for our readers - do you mark up your books, or if you collect, do you prefer marked up copies? I mean, yeah, sure, association copies are one thing, but do personal collectors prefer marked up copies? (Spoiler: I don’t like my Hertzog books to be marked up.)

RK: So interesting! As some of you know, one of the things I collect is inscribed copies of books by the bibliographer Margaret Stillwell—and I’d die for something with her annotations!

JWD: Well, I will keep an eye out for those, I’d love to see one too, then send it on to you. That was fun, Rhiannon, how about we do another one next month? And what theme have we picked?

RK: We’ll be sharing our thoughts On Cataloging. See you next month!

So, the delightful Jean Sanchez was an LHL fellow in 2019, and gave a really great talk about this concept.

Here’s something important to know - both Rhiannon and I really like Kepler (the phrase is We Stan A Kepler). And yeah, ok, there are other great astronomers, but Kepler is such a breath of fresh air after the antics of Tycho Brahe. And, no, Kepler did not murder Brahe, so don’t bring that noise here, as Thony Christie demonstrated.

Tullia d’Aragona wrote her own Dialogue on the Infinity of Love as a response to Plato’s Symposium.

Forgive me; you can take the girl out of Classics but it turns out you can’t take the Classics out of the girl…

Translation by Anne Carson.

Ok this is in quotes because let’s be honest, Italy really didn’t exist as we think of it today in 1610, but it’s a useful stand in for the competing city states that existed on the boot of Europe.

I'd somehow missed awareness on the existence of Vesalius's own annotated copy for a future edition of De Fabrica -- many thanks for pointing that out! The two author-annotated books for future editions that I stumbled across during grad school & post-grad years were Willibald Pirckheimer's translation of Ptolemy's Geography (in the Royal Society library in London) and Albrecht Dürer's copy of his Underweyssung der Messung (in the BSB-Munich). In the latter case, his annotations were accurately incorporated into a posthumous second edition, but the famous woodcut of a guy sketching a naked woman through a perspective apparatus was ironically changed from Dürer's original drawing in which the figure being sketched was most definitely male. Also "Library at Night" rules! :-)