On Training

the people who shaped us and the ideas we carry

RK: Hello and welcome back! This month we’re bringing you a short missive On Training. I’m sure I’m not alone in that one of my favorite questions to ask people is “what is your rare book origin story?” The field benefits enormously from gathering people from many different disciplines and experiences, who provide a very rich variety of expertise and ways of knowing. Coming from a background in Classics, where the structure of your education is based on everybody reading the same group of texts, I have always found this a particularly stimulating aspect of my career.

One of my graduate school professors, Amy Richlin, often emphasized to us the importance of intellectual lineage. Not cashing in on who you know or how prestigious they are, but being aware of the legacy of perspectives, knowledge, and approaches that have been passed down to you. Think of how often book descriptions mention who the author studied with. Okay, yes, sometimes you just want to be able to link up a relative unknown with somebody famous. But I think it truly is important information: it tells you right away what you might expect your author’s frame of reference to be. And sometimes, it can be a source of big surprises.

If you have intellectual parents, you also have intellectual “siblings.” The fanatical Aristotelian Cesare Cremonini taught both Girolamo Franzosi and William Harvey, who both wrote books called De motu cordis. Harvey, driven by an Aristotelian mandate to empirically explore the world, discovered how blood circulates in the body — contradicting Aristotle’s own writings. Franzosi, on the other hand, took Cremonini’s instructions to heart in a different way, and his De motu cordis sought to use Aristotle’s authority to debunk Harvey’s discovery. We all do different things with the education that we receive (for better or for worse!).

Jason, what is your origin story?

JWD: We work in circles, like you allude to, Rhiannon, that traces back to one’s advisor, or one’s committee, and I think I am going to take a lightly different track, and hopefully answer both questions about my “origin story” and lineage. But, in low key academic style, let me begin in my undergrad program - I was casting about for a major (I’d already picked studio art/photography for my minor), and took a US history course - I think it was pre-civil war(?), which was an all essay exam class. I’d adduced how to play the game of high school really well, and so wasn’t really all that challenged. Those same skills served me in early undergrad - until Mark Beasley’s class. That was the first real challenge of my academic life - arguing, with facts, and writing to a time limit. I loved that - and the attendant critical thinking skills - that I majored in history, and took several of Tiffany Fink’s classes, as well as Don Taylor’s. They taught me how to write, how to think, and really embraced the best parts of a liberal arts education. I am deeply grateful to them - but as many liberal arts majors do after graduation… I wondered what was next. I taught high school history for a few years, and after some introspection, came to librarianship as a potential career.

While I was in my library science program working at the Amon Carter, I had the privilege to meet two of my teachers: MaryJane Harbison and Ron Tyler. MaryJane helped me learn how a library works, and how to catalog, and Ron showed me what a combination of fierce scholarship and compassionate leadership looks like. Jon Frembling was also incredibly kind and generous to me, working patiently to mentor me into bigger thinking about cultural heritage. Jon and Ron ignited my passion for rare books, which I remain enthralled with.

But the real work started at Crystal Bridges, and when I met Bill Reese, who was incredibly generous with his knowledge and passion for Americana and books as objects. David Houston showed me that one doesn’t have to have a PhD to do good work and scholarship, something that has stayed with me. After I left the museum, my supervisor, Deb Kulczak, was kind and generous and supportive, showing me aspects of good leadership.

(I’m sorry if this is a crazy list - there are so many people who have given their time and passion and attention that I owe so much to!)

Moving back to Texas into a special collections leadership position really changed my perspective, and while I had a stellar colleague in Joan Parks, who taught me how to be kind and generous in the workplace - the real teachers were several of the student workers and interns I had the honor of working with: Emily Grover, Emily Higgs-Kopin, and Natalia Kapacinskas. They all expanded my academic horizons, and taught me the pleasure of watching people you support shine (and not keeping all the fun work for yourself!) All three have gone on to STELLAR careers, and I am humbled to have played a small part in that.

I suppose I should talk about the folks that have trained me in bibliography too: Jamie Cumby so kindly and generously taught me the fundamentals of descriptive bibliography. Scott Clemons has also taught me so much about books, and has been the kindest encourager I could hope for. And, I should mention, Rhiannon - you have been a guiding light for me and have taught me so much about books, and this strange corner of the world we inhabit as professionals. Of course, Nick Wilding and Paul Needham have both been endlessly patient with me and have taught me so much, it’s such an honor to work with them - as well as Christian Westergaard!

Outside of those folks, I have three really great teachers to point to - Ben Gross, who has taught me pretty much all I know about the History of Science; Jane Davis, who has taught me so much about leadership and databases and Alma and how to say hard things in a soft way. And, of course, Finch Collins keeps teaching me about compassion and joy and critical thinking in our work.

So, what is your origin story, Rhiannon? I think I know bits and pieces of it, but I’d love to hear it again! And who are you indebted to in your life with books?

RK: Well, I jumped straight into Classics as an undergraduate, for whatever mad reason. Only later did I realize how lucky and unusual my education was. My professors made the field seem so big: literature, history, ideas, objects, art—with the unifying force being Greek and Latin, which seemed like passports that could take me almost anywhere I wanted. I began interested in archaeology and the idea of “thinking with objects,” but quickly fell in love with ancient languages. It was my archaeologist advisor who pointed out to me that books are, in fact, objects made of language.

In 2010, I attended the Lincoln College summer school in Greek palaeography at Oxford, which really rocked my world. I caught a glimpse, for the first time, of where Greek “comes from.” From there I was driven by that question: where does Greek and Latin literature come from? In one sense, it comes from Ancient Greece and Rome. It comes from Indo-European. It comes from the mind. In pursuit, I studied linguistics and the philosophy of language (and wrote my undergraduate thesis on ineffability in Saint Augustine). I taught Latin to third graders. I became obsessed with Plato.

What I discovered is that, for me, it comes from books: scribes, editors, and printers.

I pursued this line of inquiry to graduate study at UCLA, where I learned that the larger field of professional Classics was not quite what I had been led to imagine from my expansive undergraduate education. Although I ended up leaving the PhD program after receiving my MA, I benefited enormously from several important teachers while I was there—all of whom, I would later realize, are book collectors. Shane Butler’s The Matter of the Page, rooted in the material reality of texts but brilliantly interested in their wider theoretical implications, was a major inspiration — and his work and friendship continues to influence the way I see the world of books. Working with medievalists Richard and Mary Rouse as a research assistant and then at the UCLA Center for Primary Research and Training, which paid me to work on the catalogue of their collection at the Charles Young Research Library, opened my world even further. They invited me into not just the library, but a whole world of dealers, auctioneers, and collectors who make knowledge about and preserve rare books.

Seeking my fortunes in the wilder world of Los Angeles, I eventually landed at the Getty Research Institute, where I spent three years and change as the research assistant of David Brafman, curator of rare books, and Marcia Reed, the chief curator. I cut my teeth on one of my greatest collections of printed rare books in the country, immersed in early modern alchemy, festival books, and travelers to China (not to mention, whatever the visiting scholars happened to be working on). David was a fellow Classicist who had strayed into other time periods, and also a former bookseller with the legendary firm H.P. Kraus. It was a natural step to move into the world of the trade, and when Christie’s was looking for a Junior Specialist in the books department, I packed my bags and returned to the East Coast (though not without some tears shed).

It is difficult to overstate the value of a Christie’s education. You see so much incredible material every single day and witness collections at every level of development. And not only that, but I was in New York: the capital city of Rare Books USA. After seven years, I feel like I finally know enough to REALLY get in trouble… but thankfully I have great colleagues to help teach me how to be a “real” bookseller.

Two Cool Things

RK: Of course, we are not only trained by people, but by books. Here’s one I encountered recently that taught me quite a bit about a subject with which I thought myself very familiar.

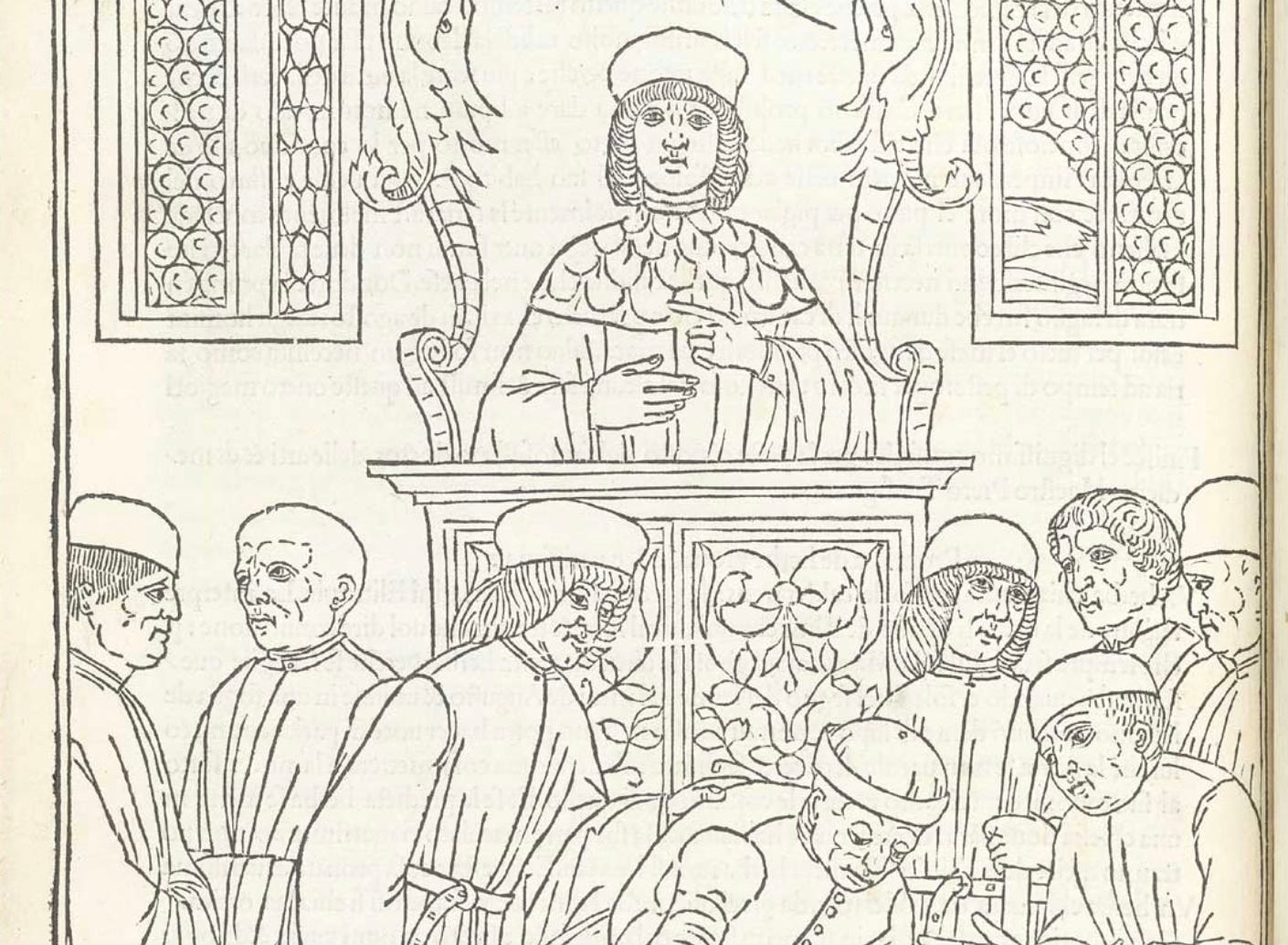

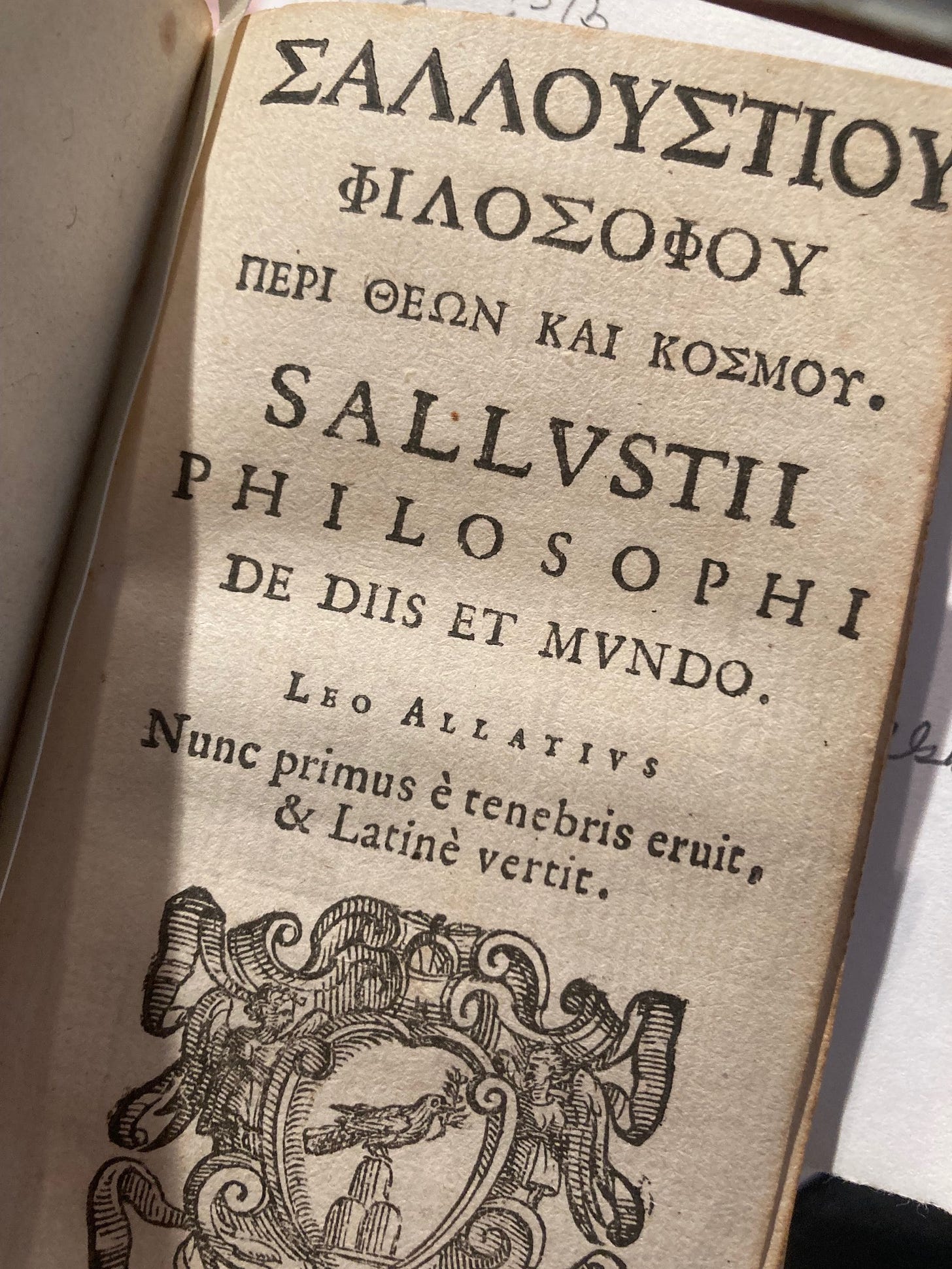

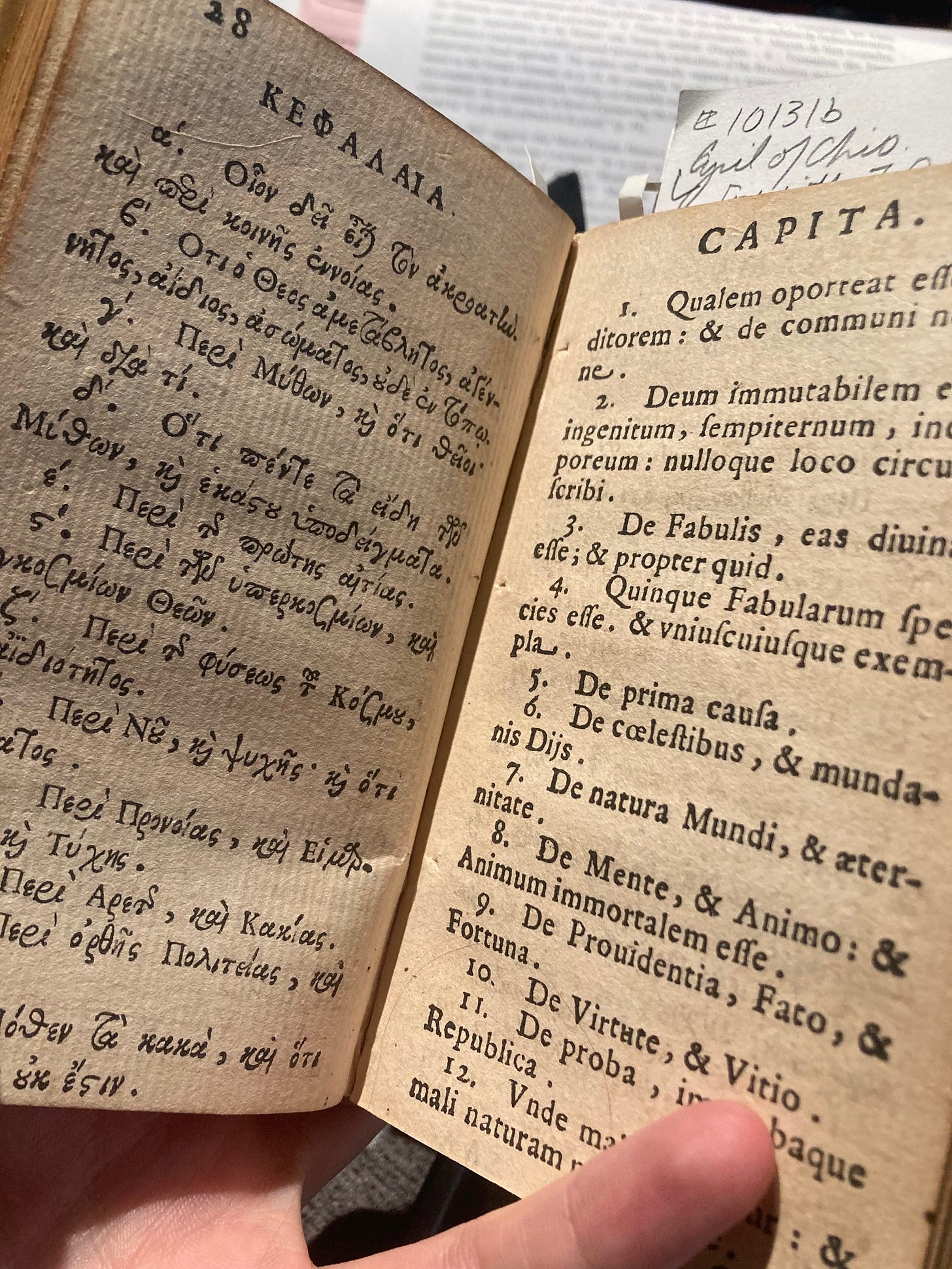

In the early 17th century, the Greek librarian and scholar Leo Allatius was working for Cardinal Barberini, in whose library he found a curious manuscript — which would later turn out to be a copy of the sole witness to an otherwise unknown ancient text: a fourth-century primer of Platonic theology. He “now for the first time plucked from the darkness and translated into Latin” the treatise, publishing it in a 1638 bilingual edition at Rome with the help of the famous French librarian and bibliophile Gabriel Naudé.

The manuscript of On The Gods and the Universe says only that it was composed by someone named “Sallustius” — now identified by scholars with close advisor of Julian the Apostate.

Julian was the last “pagan” emperor of Rome; his uncle Constantine had established Christianity as the official religion of the empire and it was catching hold fast. This text represents the last gasp of Imperial paganism, and an attempt to promote Classical philosophy in opposition to Christianity by providing the tenets of Platonism in a digestible format for non-scholars. It didn’t work, and ultimately this text was basically unread for over a thousand years — a teacher without any students.

A millennium later, this defunct guide to training new Platonists reappeared in early modern Europe with the help of Allatius and Naudé, and is dedicated to a third librarian: their friend Lucas Holstein. Holstein contributes a little commentary at the end, which provides further clarification of the various doctrines and lots of citations to Proclus and other ancient Neoplatonists.

Some of you may know that when Plato’s work was coming back into circulation in Renaissance Italy, there was drama over to what degree his writings were actually compatible with Christianity. Because Plato wrote dialogues, it was possible to be rather cagey about this. But his later followers were much more explicit about their beliefs, and our text here certainly leaves no ambiguity about some of the more controversial issues, like the eternity of the world (understandably, because the whole point was to promote Platonism against Christianity!). It really makes me curious what our illustrious librarian trio were up to here. Who was this guide for? Was their work just driven by antiquarian curiosity? Despite its heterodox content, the publication was approved by the Papal censor. But it certainly did go on to inspire more radical “pagan” thinking, including the 18th-century translator Thomas Taylor, who saw it as a serious guide to philosophy for normies:

“a beautiful epitome of the Platonic philosphy, in which the most important dogmas are delivered with such elegant conciseness, perfect accuracy, and strength of argument ... this littler work was composed by its author with a view of benefiting a middle class of mankind, whose souls are neither incurable, nor yet capable of ascending to the summit of human attainments.”

Like I said… you never know what someone is going to do with the training they get!

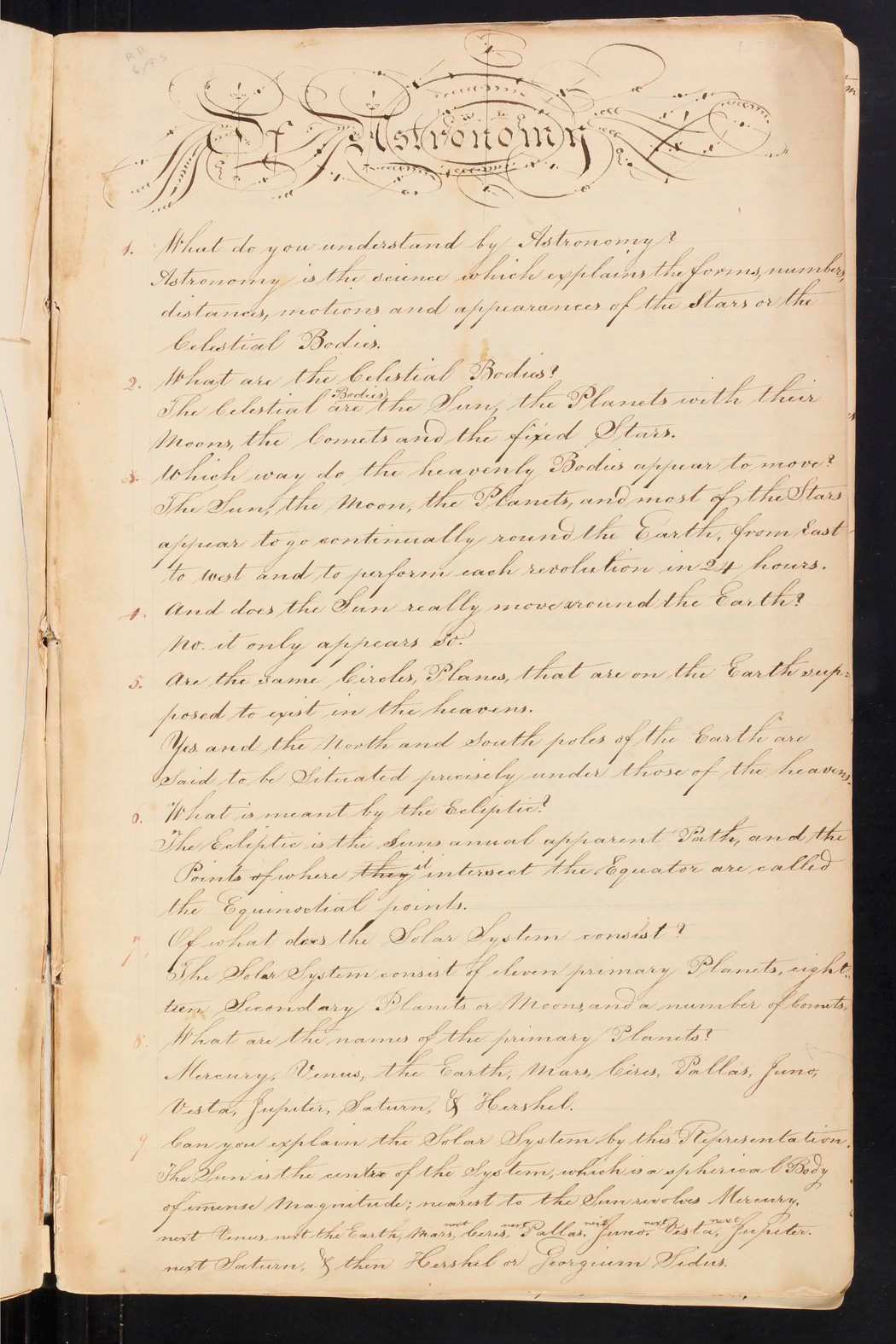

JWD: I think I am going to keep in the “on training” theme in two ways with this item - which is explicitly educational in nature, and provided a form of training for me at LHL. As I revisit it, it’s also a reminder to dig deeper into it.

This bound manuscript was the first thing I acquired for LHL, and is a fair copy book by a person we think named William Sennert, made about 1826. Why 1826? I asked the Reese Company people how they ascertained that date, and they said “that’s what Bill Reese thought,” and that’s good enough certainly for me to put in a catalog record. The cover label says, simply, “J. Beck's Astronomer, William L. Sennert's Book,” and I suspect that J. Beck is the author of a textbook, or perhaps the teacher, since Evans has no record of the book, and Worldcat has no suitable match, either.

The text is constructed in the form of a catechism, with a rhetorical question preceding 62 categorical statements about stars, planets, the solar system, and other elements of astronomy. The text is based loosely around two books, Blair's "An Easy Grammar of Natural and Experimental Philosophy," and George Gregory's "New and Complete Dictionary for the Arts and Sciences."

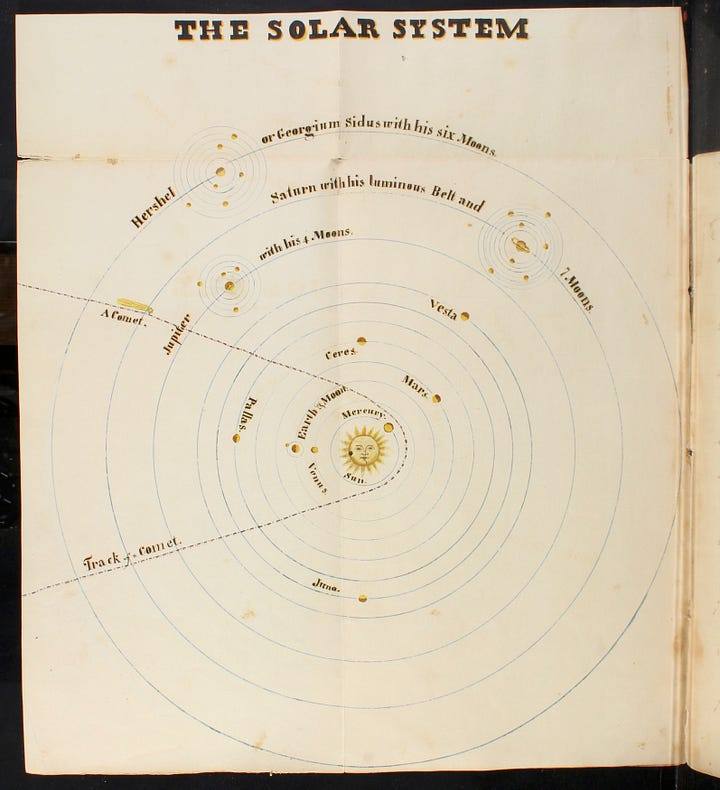

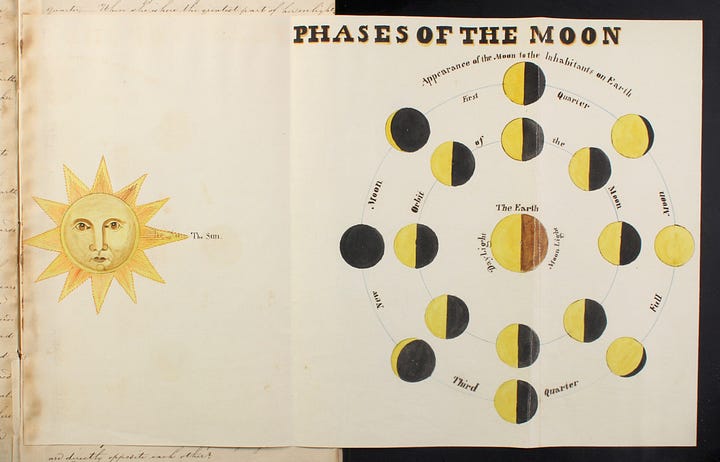

Accompanying the handwritten text are five ink and watercolor diagrams representing various planetary and star systems. The first diagram depicts the solar system to the limit of Uranus (named "Georgium Sidus," the original name of the planet given by William Herschel) and includes the dwarf planets Ceres, Pallas, Vesta, and Juno. The second image depicts the variation of day and night across the course of the year, coordinated with the signs of the Zodiac, drawn in an outer ring around the central diagram. The third drawing demonstrates the phases of the moon and the "Appearance of the Moon to the Inhabitants on Earth." The final two illustrations consist of star charts delineating Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, and Orion.

The item is clearly meant to train someone - not only in the fundamentals of astronomy, but also in penmanship and sketching. It’s a lovely thing - and note the odd orientation of the two constellations.

Current Events

RK: It’s a new school year and even though I don’t go to school, everything feels fresh and new. Nearby at the University of Pennsylvania, the new season of their Workshop in the History of the Material Text is starting on 9 September — if you aren’t nearby, don’t worry, you can watch online! Also, this isn’t exactly an event, but I recently learned, and need to share with you, that there is a series of mystery novels starring none other than Frances Yates, author of The Art of Memory and former Warburg librarian.

JWD: Friends, as you’re reading this, mine and Finch and Rebeca and Sophia and Ben and Toni’s New Acquisitions show is up at the Library - a few local news outlets picked it up, and here’s me (click through) talking about the star of the show (why not, pun intended) - the new Sidereus:

The show is on display till October 4, let me know if you’d like a tour! Fun to see all of our work come to fruition and highlight some of the key acquisitions LHL made over the last year across our collections.

I suppose you all might also like to read my most recent new acquisition blog post, on the privately printed edition of Mary Ward’s first book, Sketches with the Microscope, a really cool and charming book that I am grateful Emma Walshe of Peter Harrington made sure I saw (and helped LHL acquire!)

Let’s Get Personal

RK: For California friends, I’ll be at Booth 409 at Rare Books LA at Union Station in early October (and giving a talk about American women incunabulists at the Zamorano Club meeting, for any members)—please do come say hello! I have spent the summer working with my colleagues to produce a number of exciting catalogues which I can’t wait to show you.

JWD: My girlfriend and I will be in London and Dublin in late September and early October, we’re pretty booked but might have a moment or two to say hi and for you all to meet Aundi! I also celebrated a bachelor weekend for my middle brother, James, in Louisville recently, so here’s a photo of James and Zach at Stitzel-Weller:

Conclusion

RK: Thanks for reading! What are we talking about next time, Jason?

JWD: We’ve thought long and hard about this, Rhiannon, and since we’re past Labor Day, it seems right that our next issue will be On Ghosts, but I think we’ll likely take that in a really interesting direction, but if a ghostly/spooky book comes in the newsletter, don’t be surprised!

Really interesting to read about the legacy of our mentors, and in turn, think about our own legacies! In the field of modern astronomy it is not uncommon for coffee discussion to turn to a PhD students 'astro genealogy' and some of the current students in Armagh have big names in theirs (Including a few who by some abstract definitions of advisor/student relations claim descendancy from the Apostles). If you find yourself wandering north from Dublin, drop by the Armagh Observatory, I'd be very happy to show you some of the rare astronomical texts in our collection, and the Robinson Library has gems like the Ussher Bible and Swifts "corrected" binding of Gulliver's Travels!